library("sp")

library("spacetime")

library("ggplot2")

library("dplyr")

library("gstat")

library("RColorBrewer")

library("STRbook")

library("tidyr")4 Descriptive Spatio-Temporal Statistical Models

Chapter 3 is the linchpin for the “two Ds” of spatio-temporal statistical modeling, which are now upon us in this chapter (the first “D,” namely “descriptive”) and the next chapter (the second “D,” namely “dynamic”). We hope to have eased you from the free form of spatio-temporal exploratory data analysis presented in Chapter 2 into the “rigor” needed to build a coherent statistical model. The independent probability structure assumed in Chapter 3 was a place-holder for the sorts of probability structures that respect Tobler’s law, discussed in the previous chapters: in our context, this says that a set of values at nearby spatio-temporal locations should not be assumed independent. As we shall see, there is a “descriptive” way (this chapter, Chapter 4) and a “dynamic” way (Chapter 5) to incorporate spatio-temporal statistical dependence into models.

In this chapter we focus on two of the goals of spatio-temporal modeling given in Chapter 3: prediction at some location in space within the time span of the observations and, to a lesser extent, parameter inference for spatio-temporal covariates. For both goals we assume that our observations can be decomposed into a true (latent) spatio-temporal process plus observation error. We then assume that the true process can be written in terms of spatio-temporal fixed effects due to covariates plus a spatio-temporally dependent random process. We call this a descriptive approach because its main concern is to specify (or describe) the dependence structure in the random process. This is in contrast to the dynamic approach presented in Chapter 5 that models the evolution of the dependent random process through time. To implement the prediction and inference approaches discussed herein we must perform estimation. We mention the most popular and relevant estimation approaches and algorithms as they come up, but omit most of the details. The interested reader can explore these details in the references given in Section 4.6. Finally, we note that these discussions require a bit more statistical formality and mathematical notation, and so the presentations in this and the next chapter are at a higher technical level than those in Chapter 3.

4.1 Additive Measurement Error and Process Models

In this section we describe more formally a two-stage model that considers additive measurement error in a data (observation) model, and a process model that is decomposed into a fixed- (covariate-) effect term and a random-process term. This general decomposition is the basis for the models that we present in this and the next chapter.

Recall that at each time \(t \in \{t_1,\ldots,t_T\}\) we have \(m_{t_j}\) observations. With a slight abuse of notation, we write the number of observations at time \(t_j\) as \(m_j\). The vector of all observations is then given by

\[ \mathbf{Z}= \left(Z(\mathbf{s}_{11};t_1), Z(\mathbf{s}_{21};t_1),\ldots, Z(\mathbf{s}_{m_11};t_1),\ldots, Z(\mathbf{s}_{1T};t_T),\ldots,Z(\mathbf{s}_{m_TT};t_T)\right)'. \]

That is, different numbers of irregular spatial observations are allowed for each time (note that if there are no observations at a given time, \(t_j\), the set of spatial locations is empty for that time and \(m_j = 0\)). We seek a prediction at some spatio-temporal location \((\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)\). As described in Chapter 1, if \(t_0 < t_T\), so that we have all data available to us, then we are in a smoothing situation; if we only have data up to time \(t_0\) then we are in a filtering situation; and if \(t_0 > t_T\) then we are in a forecasting situation. We seek statistically optimal predictions for an underlying latent (i.e., hidden) random spatio-temporal process. We denote this process by \(\{Y(\mathbf{s};t): \mathbf{s}\in D_s,\ t \in D_t\}\), for spatial location \(\mathbf{s}\) in spatial domain \(D_s\) (a subset of \(d\)-dimensional Euclidean space), and time index \(t\) in temporal domain \(D_t\) (along the one-dimensional real line).

More specifically, suppose we represent the data in terms of the latent spatio-temporal process of interest plus a measurement error. For example,

\[ Z(\mathbf{s}_{ij};t_{j}) = Y(\mathbf{s}_{ij};t_j) + \epsilon(\mathbf{s}_{ij};t_{j}), \quad i=1,\ldots,m_j;\ j=1,\ldots,T, \tag{4.1}\]

where the errors \(\{\epsilon(\mathbf{s}_{ij};t_j)\}\) represent iid mean-zero measurement error that is independent of \(Y(\cdot;\cdot)\) and has variance \(\sigma^2_\epsilon\). So, in the simple data model Equation 4.1 we assume that the data are noisy observations of the latent process \(Y\) at a finite collection of locations in the space-time domain, where typically we have not observed data at all locations of interest. Consequently, we would like to predict the latent value \(Y(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)\) at a spatio-temporal location \((\mathbf{s}_{0};t_0)\) as a function of the data vector represented by \(\mathbf{Z}\) (or some subset of these observations), which is of dimension \(\sum_{j=1}^T m_j\). To simplify the notation that follows, we shall sometimes assume that data were observed at the same set of \(m\) locations for each of the \(T\) times, in which case \(\mathbf{Z}\) is of length \(m T\).

Now suppose that the latent process follows the model

\[ Y(\mathbf{s};t) = \mu(\mathbf{s};t) + \eta(\mathbf{s};t), \tag{4.2}\]

for all \((\mathbf{s};t)\) in our space-time domain of interest (e.g., \(D_s \times D_t\)), where each component in Equation 4.2 has a special role to play. In Equation 4.2, \(\mu(\mathbf{s};t)\) represents the process mean, which is not random, and \(\eta(\mathbf{s};t)\) represents a mean-zero random process with spatial and temporal statistical dependence. Our goal here is to find the optimal linear predictor in the sense that it minimizes the mean squared prediction error between \(Y(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)\) and our prediction, which we write as \(\widehat{Y}(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0).\) Depending on the problem at hand, we may choose to let \(\mu(\mathbf{s};t)\) be: (i) known, (ii) constant but unknown, or (iii) modeled in terms of \(p\) covariates, \(\mu(\mathbf{s};t) = \mathbf{x}(\mathbf{s};t)'\boldsymbol{\beta}\), where the \(p\)-dimensional vector of parameters \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) is unknown. In the context of the descriptive methods considered in this chapter, these choices result in spatio-temporal (S-T) (i) simple, (ii) ordinary, and (iii) universal kriging, respectively. Note that in this and subsequent chapters, the covariate vector \(\mathbf{x}(\mathbf{s};t)\) could include the variable “1,” which models an intercept in the multivariable regression.

4.2 Prediction for Gaussian Data and Processes

Recall from Chapter 3 that when we interpolate with spatio-temporal data we specify that the value of the process at some location is simply a weighted combination of nearby observations. We described a couple of deterministic methods to obtain such weights (inverse distance weighting and kernel smoothing). Here we are concerned with determining the statistically “optimal” weights in this linear combination. At this point, it is worth taking a step back and looking at the big picture.

In the case of predicting statistically within the domain of our space-time observation locations (smoothing), we are just interpolating our observations \(\mathbf{Z}\) to the location \((\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)\) in a way that respects that we have observational uncertainty. For example, in the special case where \((\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)\) corresponds to an observation location, we are simply smoothing out this observation uncertainty. Unlike the deterministic approaches to spatio-temporal prediction in Chapter 3, we seek the weights in a linear predictor that minimize the interpolation error on average. This optimization criterion is \(E(Y(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0) - \widehat{Y}(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0))^2\), the mean square prediction error (MSPE). The best linear unbiased predictor that minimizes the MSPE is referred to as the kriging predictor. As we shall see, the kriging weights are determined by the statistical dependence (i.e., covariances) between observation locations (roughly, the greater the covariability, the greater the weight), yet respect the measurement uncertainty.

There are several different approaches to deriving the form of the optimal linear predictor, which we henceforth call S-T . Given that we are just focusing on the first two moments in the descriptive approach (i.e., the means, variances, and covariances of \(Y(\cdot;\cdot)\)), it is convenient to assume that the underlying process is a Gaussian process and the has a Gaussian distribution. We take this approach in this book.

What is a Gaussian process? Consider a stochastic process denoted by \(\{Y(\mathbf{r}): \mathbf{r}\in D\}\), where \(\mathbf{r}\) is a spatial, temporal, or spatio-temporal location in \(D\), a subset of \(d\)-dimensional space. This process is said to be a Gaussian process, often denoted \(Y(\mathbf{r}) \sim GP(\mu(\mathbf{r}), c(\cdot;\cdot))\), if the process has all its finite-dimensional distributions Gaussian, determined by a mean function \(\mu(\mathbf{r})\) and a covariance function \(c(\mathbf{r},\mathbf{r}') = \textrm{cov}(Y(\mathbf{r}),Y(\mathbf{r}'))\) for any location \(\{\mathbf{r},\mathbf{r}'\} \in D\). (Note that in spatio-temporal statistics it is common to use \(Gau(\cdot,\cdot)\) instead of \(GP(\cdot,\cdot)\), and we follow that convention in this book.) There are two important points to make about the Gaussian process. First, because the Gaussian process determines a probability distribution over functions, it exists everywhere in the domain of interest \(D\); so, if the mean and covariance functions are known, the process can be described anywhere in the domain. Second, only finite distributions need to be considered in practice because of the fundamental property that any finite collection of Gaussian process random variables \(\{Y(\mathbf{r}_i)\}\) has a joint multivariate normal (Gaussian) distribution. This allows the use of traditional machinery of multivariate normal distributions when performing prediction and inference. Gaussian processes are fundamental to the theoretical and practical foundation of spatial and spatio-temporal statistics and, since the first decade of the twenty-first century, have become increasingly important and popular modeling tools in the machine-learning community (e.g., Rasmussen & Williams, 2006).

In the context of S-T , time is implicitly treated as another dimension, and we consider covariance functions that describe covariability between any two space-time locations (where in general we should use covariance functions that respect that durations in time are different from distances in space). We can write the data model in terms of vectors,

\[ \mathbf{Z}= \mathbf{Y}+ \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}, \tag{4.3}\]

where \(\mathbf{Y}\equiv (Y(\mathbf{s}_{11};t_1),\ldots,Y(\mathbf{s}_{m_TT};t_T))'\) and \(\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}\equiv (\epsilon(\mathbf{s}_{11};t_1),\ldots,\epsilon(\mathbf{s}_{m_TT};t_T))'\). Similarly, the vector form of the process model for \(\mathbf{Y}\) is written

\[ \mathbf{Y}= \boldsymbol{\mu}+ \boldsymbol{\eta}, \tag{4.4}\]

where \(\boldsymbol{\mu}\equiv (\mu(\mathbf{s}_{11};t_1),\ldots,\mu(\mathbf{s}_{m_TT};t_T))' = \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta}\), and \(\boldsymbol{\eta}\equiv (\eta(\mathbf{s}_{11};t_1),\ldots,\eta(\mathbf{s}_{m_TT};t_T))'\). Note that \(\textrm{cov}({\mathbf{Y}}) \equiv \mathbf{C}_y = \mathbf{C}_\eta\), \(\textrm{cov}({\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}}) \equiv \mathbf{C}_{\epsilon}\), and \(\textrm{cov}({\mathbf{Z}}) \equiv \mathbf{C}_z = \mathbf{C}_y + \mathbf{C}_{\epsilon}\).

Now, defining \(\mathbf{c}_0' \equiv \textrm{cov}(Y(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0),{\mathbf{Z}})\), \(c_{0,0} \equiv \textrm{var}(Y(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0))\), and \(\mathbf{X}\) the \((\sum_{j=1}^T m_j) \times p\) matrix given by \(\mathbf{X}\equiv [\mathbf{x}(\mathbf{s}_{ij};t_j)': i=1,\ldots,m_j;\ j=1,\ldots,T]\), consider the joint Gaussian distribution,

\[ \left[\begin{array}{c} Y(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0) \\ \mathbf{Z}\end{array}\right] \; \sim \; Gau\left(\left[\begin{array}{c} \mathbf{x}(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)' \\ \mathbf{X}\end{array}\right] \boldsymbol{\beta}\; , \; \left[\begin{array}{cc} c_{0,0} & \mathbf{c}_0' \\ \mathbf{c}_0 & \mathbf{C}_z \end{array}\right] \right). \]

Using well-known results for conditional distributions from a joint multivariate normal (Gaussian) distribution (e.g., Johnson & Wichern, 1992), and assuming (for the moment) that \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) is known (recall that this is called S-T simple kriging), one can obtain the conditional distribution,

\[ Y(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0) \; \mid \mathbf{Z}\; \sim \; Gau(\mathbf{x}(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)'\boldsymbol{\beta}+ \mathbf{c}_0' \mathbf{C}_z^{-1} (\mathbf{Z}- \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta})\; , \; c_{0,0} - \mathbf{c}_0' \mathbf{C}_z^{-1} \mathbf{c}_0), \tag{4.5}\]

for which the mean is the S-T simple kriging predictor,

\[ \widehat{Y}(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0) = \mathbf{x}(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)'\boldsymbol{\beta}+ \mathbf{c}_0' \mathbf{C}_z^{-1} (\mathbf{Z}- \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta}), \tag{4.6}\]

and the variance is the S-T simple kriging variance,

\[ \sigma^2_{Y,sk}(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0) = c_{0,0} - \mathbf{c}_0' \mathbf{C}_z^{-1} \mathbf{c}_0. \tag{4.7}\]

Note that we call \(\sigma_{Y,sk}(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)\) the S-T simple kriging prediction standard error, and it has the same units as \(\widehat{Y}(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)\).

It is fundamentally important in kriging that one be able to specify the covariance between the process at any two locations in the domain of interest (i.e., \(\mathbf{c}_0\)). That is, we assume that the process is defined for an uncountable set of locations and the data correspond to a partial realization of this process. As mentioned above, this is the benefit of considering S-T kriging from the Gaussian-process perspective. That is, if we assume we have a Gaussian process, then we can specify a valid finite-dimensional Gaussian distribution for any finite subset of locations.

Another important observation to make here is that Equation 4.6 is a predictor of the hidden value, \(Y(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)\), not of \(Z(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)\). The form of the conditional distribution given by Equation 4.5 helps clarify the intuition behind S-T kriging. In particular, note that the conditional mean takes the residuals between the observations and their marginal means (i.e., \(\mathbf{Z}- \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta}\)), weights them according to \(\mathbf{w}' \equiv \mathbf{c}_0' \mathbf{C}_z^{-1}\), and adds the result back onto the marginal mean corresponding to the prediction location (i.e., \(\mathbf{x}(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)'\boldsymbol{\beta}\)). Furthermore, the weights, \(\mathbf{w}\), are only a function of the covariances and the measurement-error variance. Another way to think of this is that the trend term \(\mathbf{x}(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)' \boldsymbol{\beta}\) is the mean of \(Y(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)\) prior to considering the observations; then the simple S-T kriging predictor combines this prior mean with a weighted average of the mean-corrected observations to get a new, conditional, mean. Similarly, if one interprets \(c_{0,0}\) as the variance prior to considering the observations, then the conditional (on the data) variance reduces this initial variance by an amount given by \(\mathbf{c}_0' \mathbf{C}_z^{-1} \mathbf{c}_0\). Consider the following numerical example.

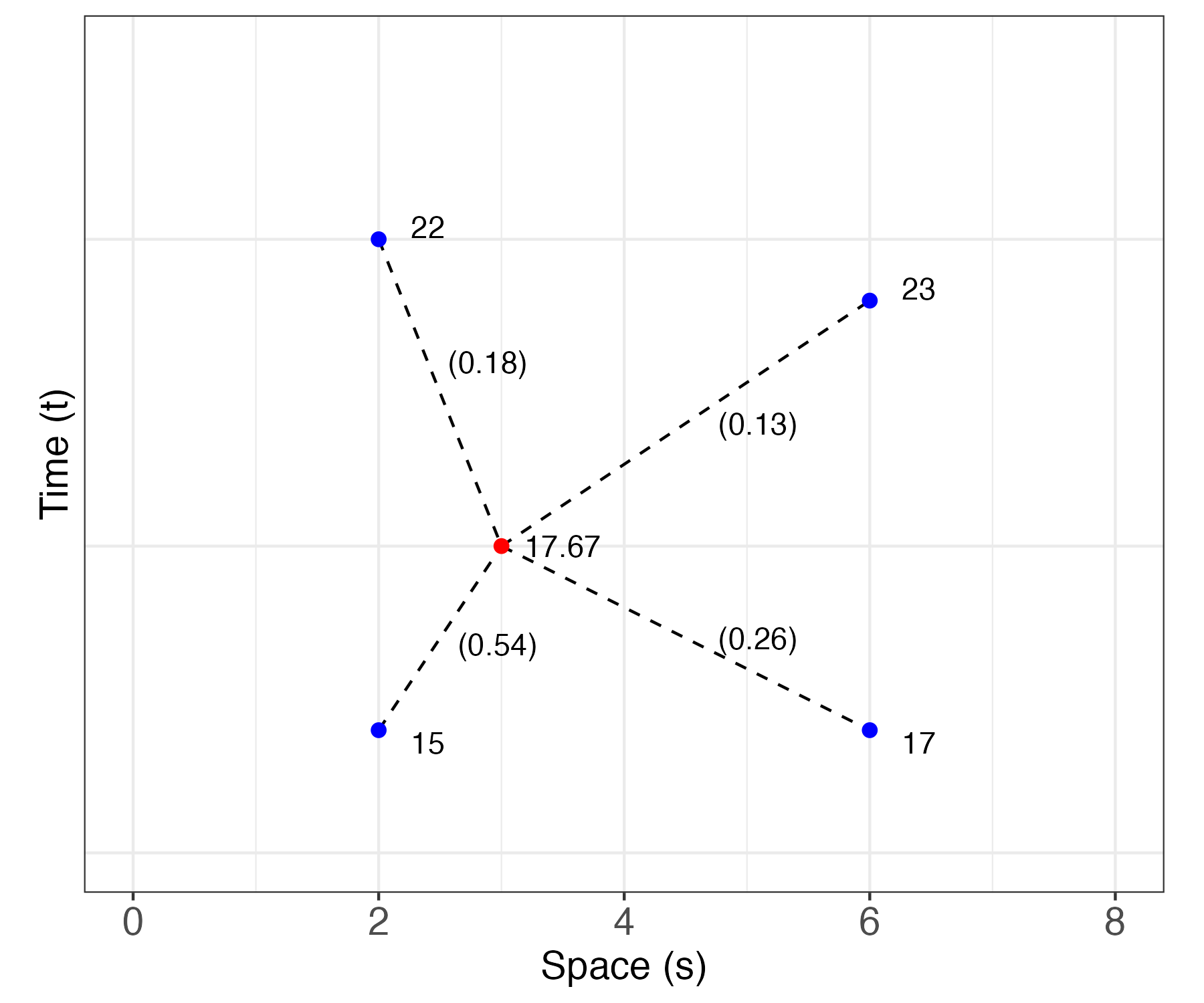

Example: Simple S-T Kriging

Suppose we have four observations in a one-dimensional space and a one-dimensional time domain: \(Z(2;0.2) = 15\), \(Z(2;1.0) = 22\), \(Z(6;0.2) = 17\), and \(Z(6;0.9) = 23\). We seek an S-T simple kriging prediction for \(Y(s_0;t_0) = Y(3;0.5)\). The data locations and prediction location are shown in Figure 4.1. Let \(x(s;t) = 1\) for all \(s\) and \(t\), \(\beta = 20\), and \(\textrm{var}(Y(s;t)) = 2\) for all \(s\) and \(t\). Using the spatio-temporal covariance function Equation 4.13 discussed below (with parameters \(a=2\), \(b=0.2\), \(\sigma^2 = c_{0,0} = 2.0\), and \(d=1\)), the covariance (between data) matrix \(\mathbf{C}_z\), the covariance (between the data and the latent \(Y(\cdot;\cdot)\) at the prediction location) vector \(\mathbf{c}_0\), and the weights \(\mathbf{w}' = \mathbf{c}_0' \mathbf{C}_z^{-1}\) are given by

\[ \mathbf{C}_z = \left[\begin{array}{rrrr} 2.0000 & 1.0600 & 1.0546 & 0.9364 \\ 1.0600 & 2.0000 & 0.8856 & 1.0599 \\ 1.0546 & 0.8856 & 2.0000 & 1.1625 \\ 0.9364 & 1.0599 & 1.1625 & 2.0000 \end{array} \right], \;\; \mathbf{c}_0 = \left[\begin{array}{r} 1.6653 \\ 1.3862 \\ 1.3161 \\ 1.2539 \end{array} \right], \;\; \mathbf{w}= \left[\begin{array}{r} 0.5377 \\ 0.2565 \\ 0.1841 \\ 0.1323 \end{array} \right]. \]

Substituting these matrices, vectors, and the data vector, \(\mathbf{Z}= (15,22,17,23)'\), into the formulas for the S-T kriging predictor Equation 4.6 and prediction variance Equation 4.7, we obtain

\[ \begin{aligned} \widehat{Y}(3;0.5) &= 17.67, \\ \widehat{\sigma}^2_{Y,sk} &= 0.34. \end{aligned} \]

Note that the S-T simple kriging prediction \((17.67)\) is substantially smaller than the prior mean \((20)\), mainly because the highest weights are associated with the earlier times, which have smaller values. In addition, the S-T simple kriging prediction variance (\(0.34\)) is much less than the prior variance \((2)\), as expected when there is strong spatio-temporal dependence.

In most real-world problems, one would not know \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\). In this case, our optimal prediction problem is analogous to the estimation of effects in a linear mixed model, that is, in a model that considers the response in terms of both fixed effects (e.g., regression terms) and random effects, \(\boldsymbol{\eta}\). It is straightforward to show that the optimal linear unbiased predictor, or S-T universal kriging predictor of \(Y(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)\) is

\[ \widehat{Y}(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0) = \mathbf{x}(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)' \widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathrm{gls}} + \mathbf{c}_0' \mathbf{C}_z^{-1} (\mathbf{Z}- \mathbf{X}\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathrm{gls}}), \tag{4.8}\]

where the generalized least squares (gls) estimator of \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) is given by

\[ \widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathrm{gls}} \equiv (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{C}_z^{-1} \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{C}_z^{-1} \mathbf{Z}. \tag{4.9}\]

The associated S-T universal kriging variance is given by

\[ \sigma^2_{Y,\mathrm{uk}}(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0) = c_{0,0} - \mathbf{c}_0' \mathbf{C}_z^{-1} \mathbf{c}_0 + \kappa, \tag{4.10}\]

where

\[ \kappa \equiv (\mathbf{x}(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0) - \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{C}_z^{-1} \mathbf{c}_0)' (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{C}_z^{-1} \mathbf{X})^{-1} (\mathbf{x}(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0) - \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{C}_z^{-1} \mathbf{c}_0) \]

represents the additional uncertainty brought to the prediction (relative to S-T simple kriging) due to the estimation of \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\). We call \(\sigma_{Y,\mathrm{uk}}(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0)\) the S-T universal kriging prediction standard error.

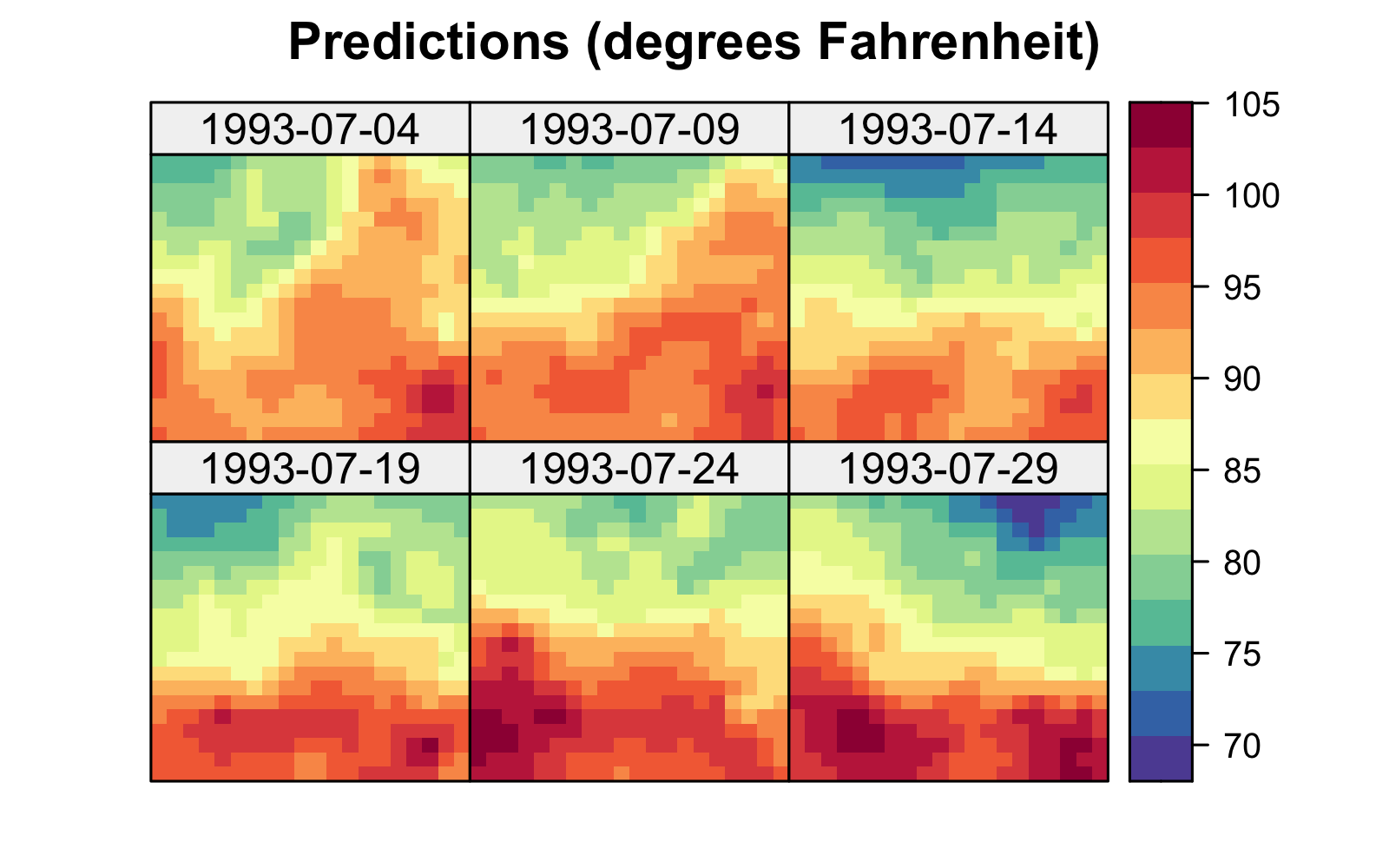

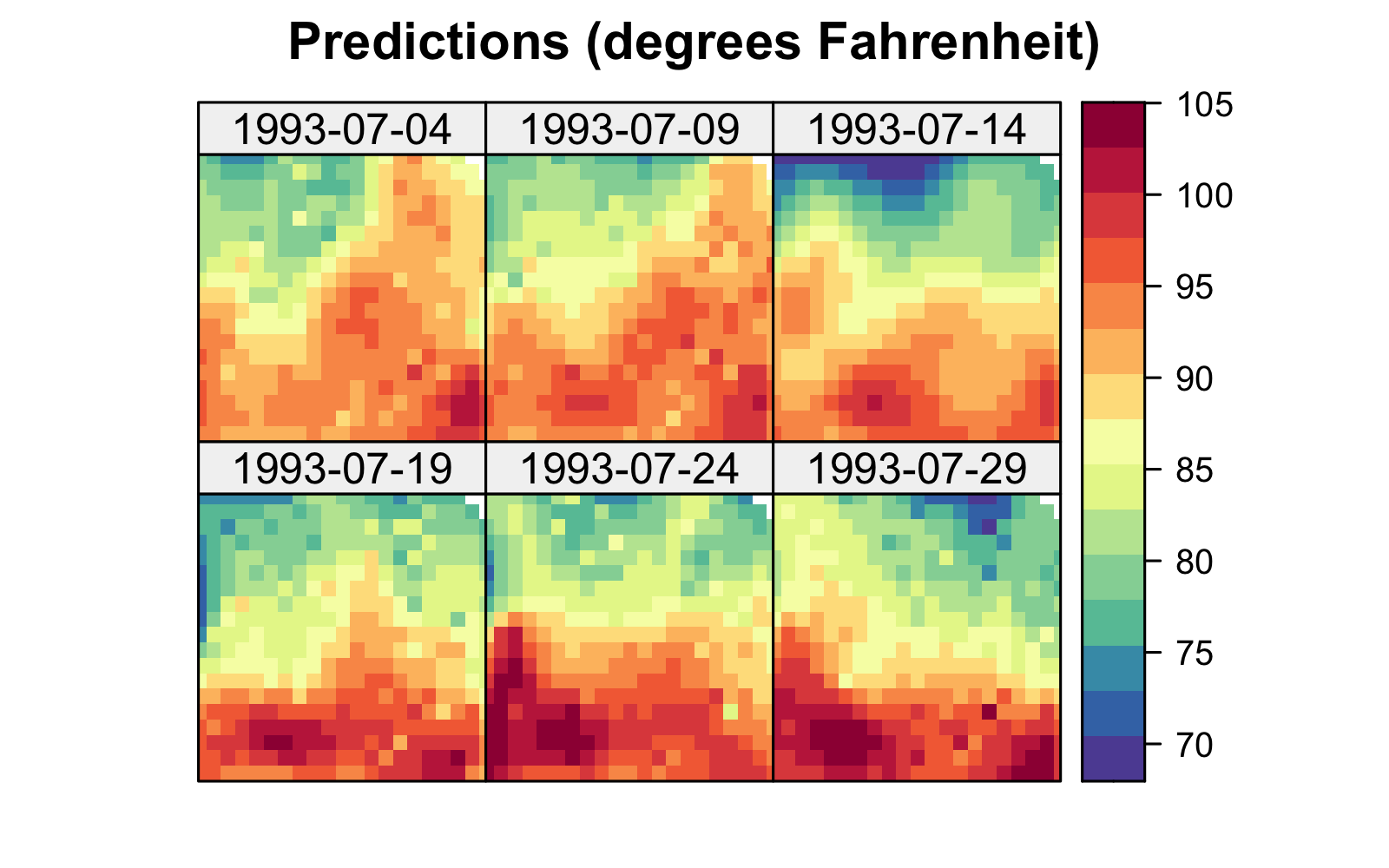

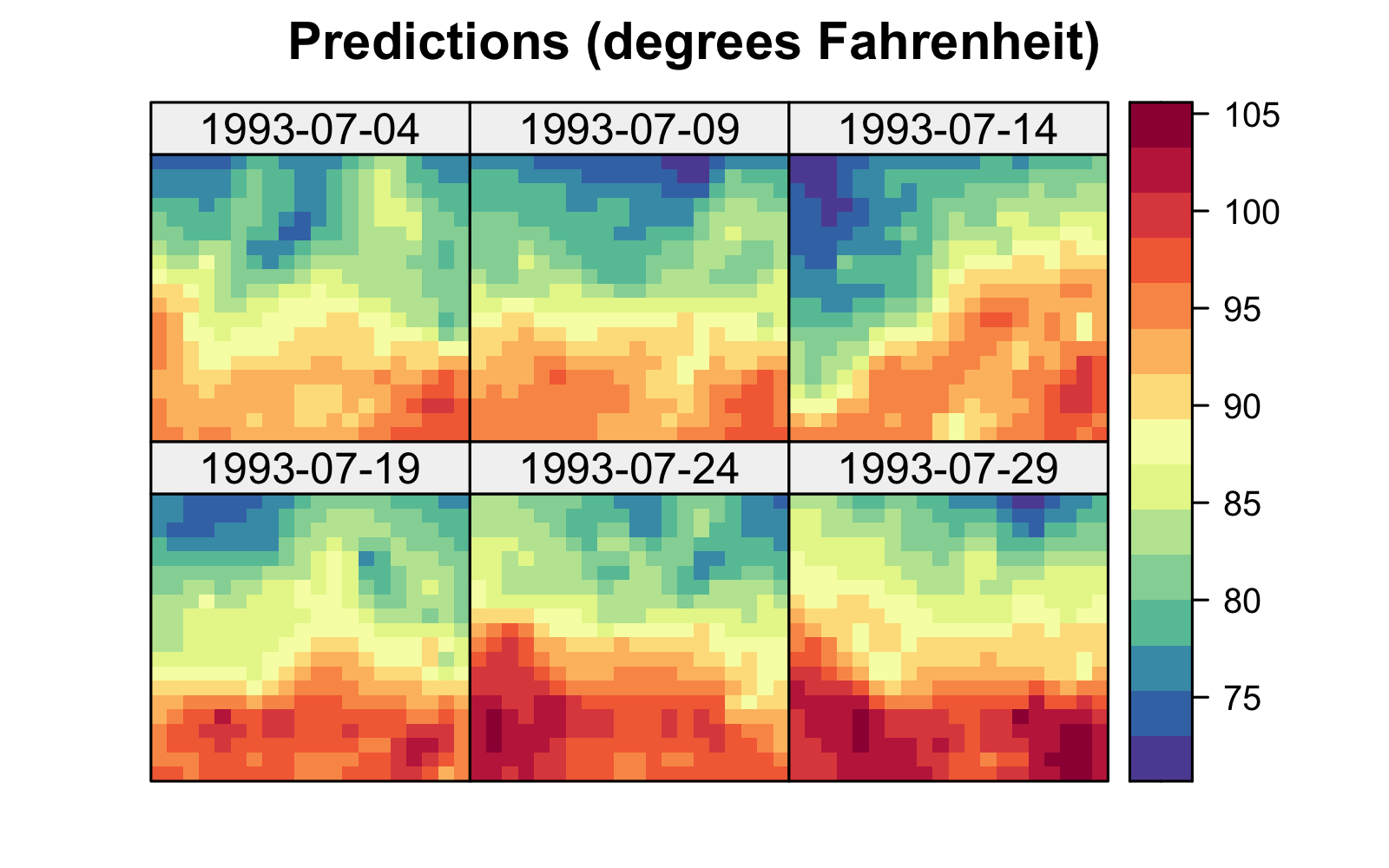

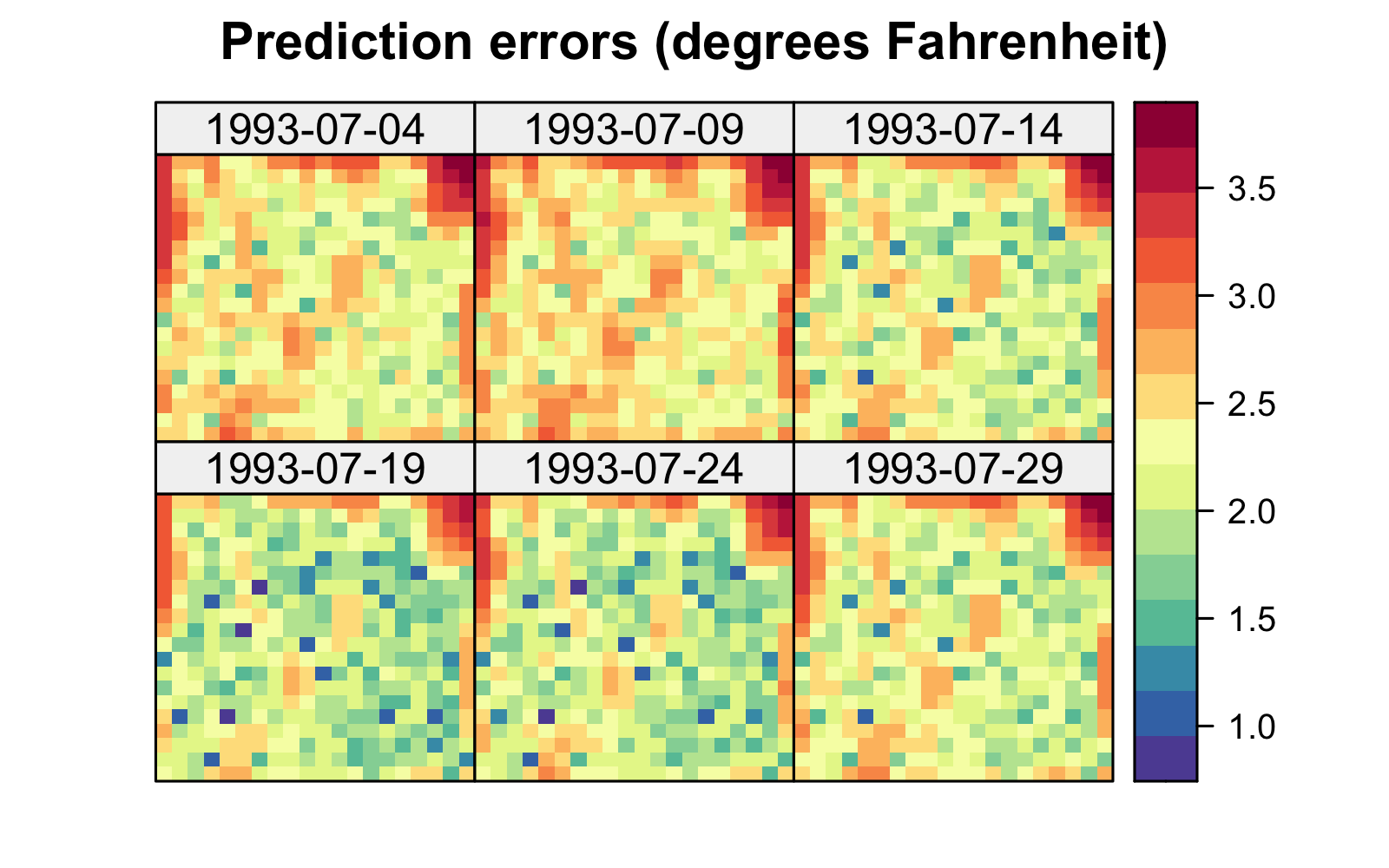

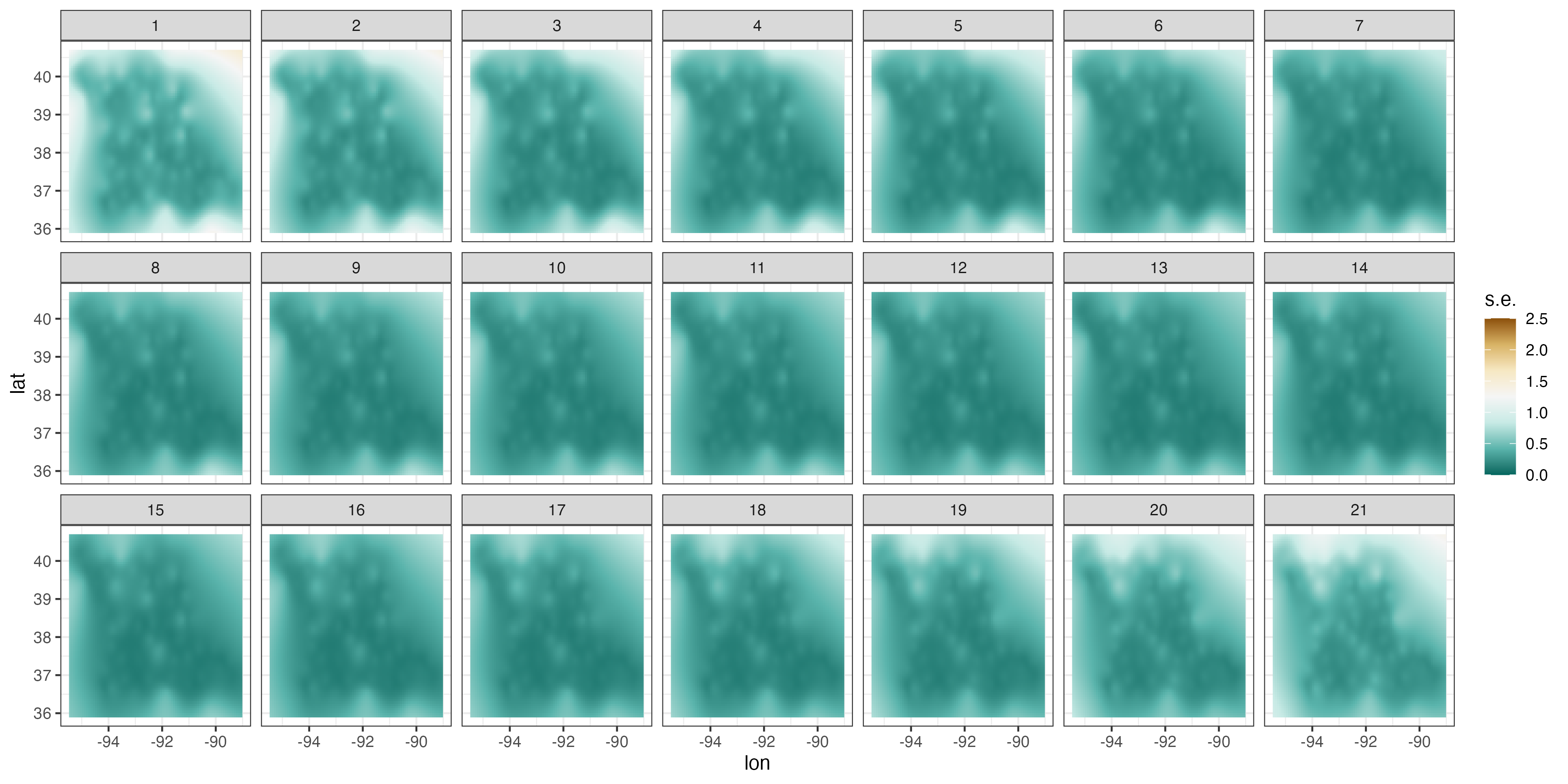

Both the S-T simple and universal kriging equations can be extended easily to accommodate prediction at many locations in space and time, including those at which we have observations. For example, in Figure 4.2, we show predictions of maximum temperature from data in the NOAA data set in July 1993 on a space-time grid (using a separable spatio-temporal covariance function, defined in Section 4.2.1), with 14 July deliberately omitted from the data set. The respective prediction standard errors are shown in Figure 4.2, where those for 14 July are substantially larger. We produce these figures in Lab 4.1.

For readers who have some experience with spatial statistics, particularly geostatistics, the development given above in the spatio-temporal context will look very familiar. S-T simple, ordinary, and universal are the same as their spatial counterparts, but now in space and time.

So far, we have assumed that we know the variances and covariances that make up \(\mathbf{C}_y\), \(\mathbf{C}_\epsilon\) (recall that \(\mathbf{C}_z = \mathbf{C}_y + \mathbf{C}_\epsilon\)), \(\mathbf{c}_0\), and \(c_{0,0}\). Of course, in reality we would rarely (if ever) know these. The seemingly simple solution is to parameterize them, say in terms of parameters \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\), and then estimate them through maximum likelihood, restricted maximum likelihood (see Note 4.2) as in the classical linear mixed model, or perhaps through a fully implementation, in which case one specifies prior distributions for the elements of \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) (see Section 4.2.3). As in spatial statistics, the parameterization of these covariance functions is one of the most challenging problems in spatio-temporal statistics.

4.2.1 Spatio-Temporal Covariance Functions

We saw in the previous section that S-T predictors require that we know \(\mathbf{C}_z\) and \(\mathbf{c}_0\), and hence we need to know the spatio-temporal covariances between the hidden random process evaluated at any two locations in space and time. It is important to note that not any function can be used as a covariance function. Let a general spatio-temporal covariance function be denoted by

\[ c_*(\mathbf{s},\mathbf{s}';t,t') \equiv \textrm{cov}(Y(\mathbf{s};t),Y(\mathbf{s}';t')), \tag{4.11}\]

which is appropriate only if the function is valid (i.e., non-negative-definite, which guarantees that the variances are non-negative). (Note that in Equation 4.11 the primes are not transposes, but are used to denote different spatio-temporal locations.)

In practice, classical- implementations assume second-order stationarity: the random process is said to be second-order (or weakly) stationary if it has a constant expectation \(\mu\) (say) and a covariance function that can be expressed in terms of spatial and temporal lags:

\[ c_*(\mathbf{s},\mathbf{s}';t,t') = c(\mathbf{s}' - \mathbf{s}; t' - t) = c(\mathbf{h}; \tau), \]

where \(\mathbf{h}\equiv \mathbf{s}' - \mathbf{s}\) and \(\tau \equiv t - t'\) are the spatial and temporal lags, respectively. Recall from Chapter 2 that if the dependence on spatial lag is only a function of \(||\mathbf{h}||\), we say there is spatial . Arguably, the two biggest benefits of the second-order stationarity assumption are that it allows for more parsimonious parameterizations of the covariance function, and that it provides pseudo-replication of dependencies at given lags in space and time, both of which facilitate estimation of the covariance function’s parameters. \((\)In practice, it is unlikely that the spatio-temporal stationary covariance function is completely known and it is usually specified in terms of some parameters \(\boldsymbol{\theta}.)\)

The next question is how to obtain valid stationary (or non-stationary) spatio-temporal covariance functions. Mathematically speaking, how do we ensure that the functions we choose are non-negative-definite?

Separable (in Space and Time) Covariance Functions

Separable classes of spatio-temporal covariance functions have often been used in spatio-temporal modeling because they offer a convenient way to guarantee validity. The class is given by

\[ c(\mathbf{h};\tau) \equiv c^{(s)}(\mathbf{h}) \cdot c^{(t)}(\tau), \]

which is valid if both the spatial covariance function, \(c^{(s)}(\mathbf{h})\), and the temporal covariance function, \(c^{(t)}(\tau)\), are valid. There are a large number of classes of valid spatial and valid temporal covariance functions in the literature (e.g., the Matérn, power exponential, and Gaussian classes, to name a few). For example, the exponential covariance function (which is a special case of both the Matérn covariance function and the power exponential covariance function) is given by

\[ c^{(s)}(\mathbf{h}) = \sigma_s^2 \exp\left\{- \frac{||\mathbf{h}||}{a_s} \right\}, \]

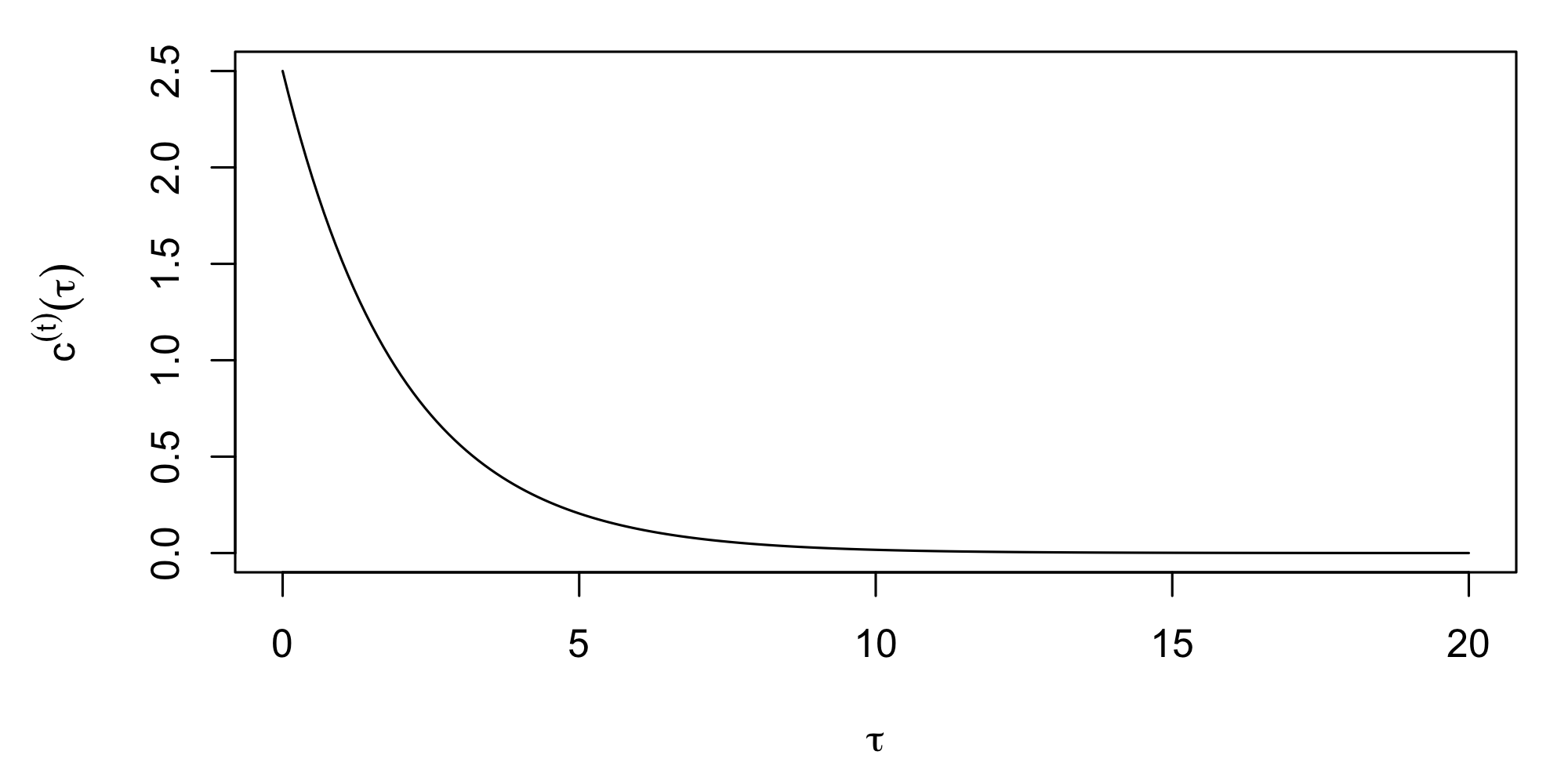

where \(\sigma_s^2\) is the variance parameter and \(a_s\) is the spatial-dependence (or scale) parameter in units of distance. The larger \(a_s\) is, the more dependent the spatial process is. Similarly, \(c^{(t)}(\tau) = \sigma_t^2 \exp\{-|\tau|/a_t\}\) is a valid temporal covariance function (see Figure 4.3 for an example).

A consequence of separability is that the resulting spatio-temporal correlation function, \(\rho(\mathbf{h};\tau) \equiv c(\mathbf{h};\tau)/c({\mathbf{0}};0)\), is given by

\[ \rho(\mathbf{h};\tau) = \rho^{(s)}(\mathbf{h};0) \cdot \rho^{(t)}({\mathbf{0}};\tau), \]

where \(\rho^{(s)}(\mathbf{h};0)\) and \(\rho^{(t)}({\mathbf{0}};\tau)\) are the corresponding marginal spatial and temporal correlation functions, respectively. Thus, one only needs the marginal spatial and temporal correlation functions to obtain the joint spatio-temporal correlation function under separability. In addition, models facilitate computation. Notice (e.g., from Equation 4.6 and Equation 4.7) that the inverse \(\mathbf{C}_z^{-1}\) is ubiquitous in S-T equations. Separability can allow one to consider the inverse of the spatial and temporal components separately. For example, assume that \(Z(\mathbf{s}_{ij};t_j)\) is observed at the same \(i=1,\ldots,m_j = m\) locations at each time point, \(j=1,\ldots,T\). In this case, one can write \(\mathbf{C}_z = \mathbf{C}_z^{(t)} \otimes \mathbf{C}_z^{(s)}\), where \(\otimes\) is the (see Note 4.1), \(\mathbf{C}_z^{(t)}\) is the \(T \times T\) temporal covariance matrix, and \(\mathbf{C}_z^{(s)}\) is the \(m \times m\) spatial covariance matrix. Taking advantage of a useful property of s (see Note 4.1), \(\mathbf{C}_z^{-1} = (\mathbf{C}_z^{(t)})^{-1} \otimes (\mathbf{C}_z^{(s)})^{-1}\), which shows that to take the inverse of the \(m T \times m T\) matrix \(\mathbf{C}_z\), one only has to take the inverses of \(T \times T\) and \(m \times m\) matrices.

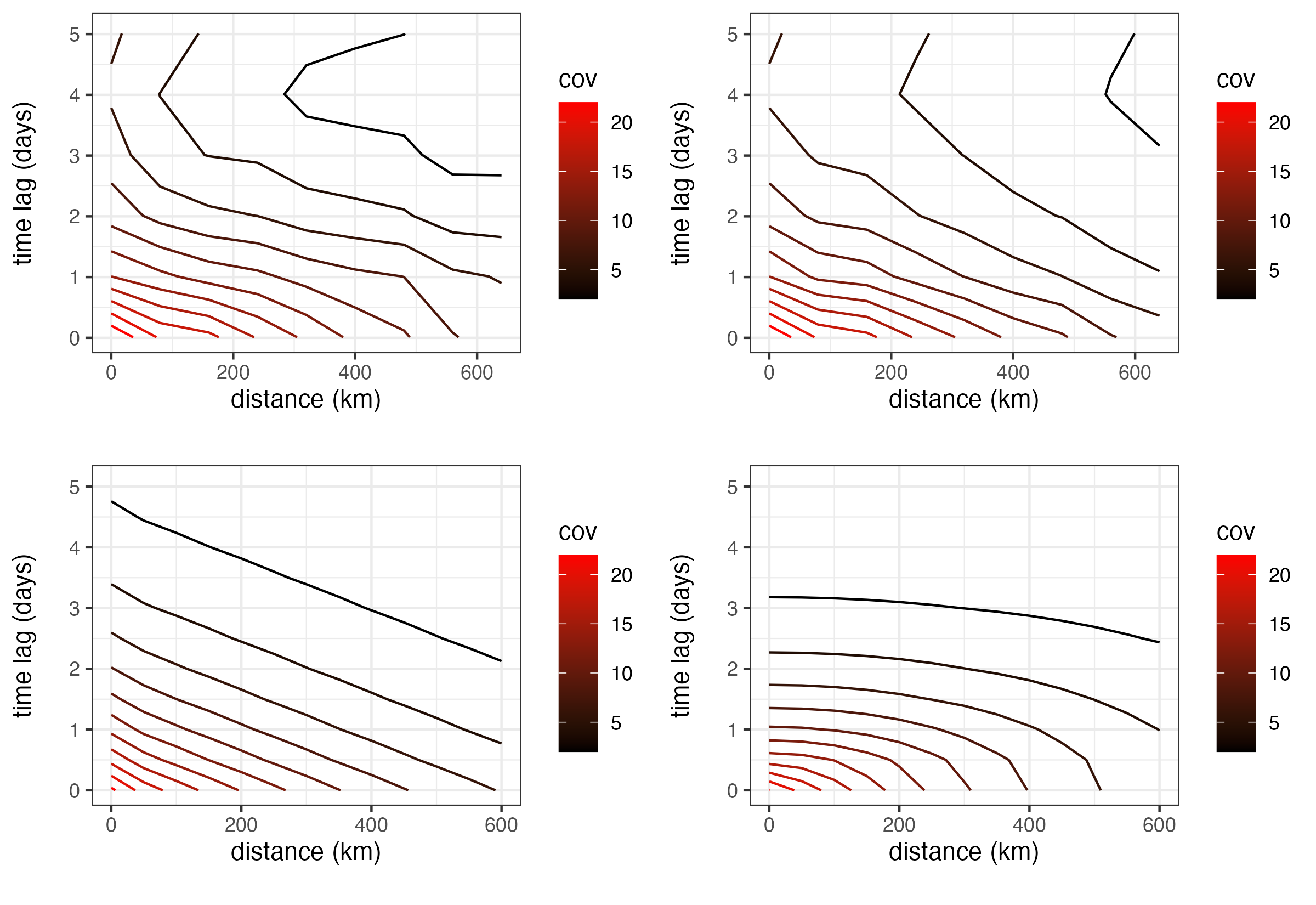

Consider the maximum-temperature observations (Tmax) from the NOAA data set presented in Chapter 2. After removing the obvious linear trend in latitude, we consider the empirical isotropic spatio-temporal covariance function (discussed in Section 2.4.2) calculated for the residuals, shown in Figure 4.4 (top left panel), and we compare that to the empirical model in Figure 4.4 (top right panel). That is, we are simply considering the product of \(\hat{c}(0;|\tau|)\) and \(\hat{c}(\|\mathbf{h}\|;0)\). Note that these two plots are remarkably similar, giving visual support for a model in this case. We shall discuss the lower two panels of this figure in Section 4.2.3. See Crujeiras et al. (2010) and references therein for formal tests of separability.

A consequence of the separability property is that the temporal evolution of the process at a given spatial location does not depend directly on the process’ temporal evolution at other locations. As we discuss in Chapter 5, this is very seldom the case for real-world processes as it implies no interaction across space and time. The question then becomes, “how can we obtain other classes of spatio-temporal covariance functions?” Several approaches that have been developed in the literature: (i) sums-and-products formulation; (ii) construction by a spectral representation through Bochner’s theorem (which formally relates the spectral representation to the covariance representation; e.g., the inverse Fourier transform is a special case); and (iii) covariance functions from the solution of stochastic partial differential equations (SPDEs). We discuss these briefly below.

Consider two matrices, an \(n_a \times m_a\) matrix, \(\mathbf{A}\), and an \(n_b \times m_b\) matrix, \(\mathbf{B}\). The Kronecker product is given by the \(n_a n_b \times m_a m_b\) matrix \(\mathbf{A}\otimes \mathbf{B}\) defined as \[ \mathbf{A}\otimes \mathbf{B}= \left[\begin{array}{ccc} a_{11} \mathbf{B}& \cdots & a_{1 m_a} \mathbf{B}\\ \vdots & \vdots & \vdots \\ a_{n_a 1} \mathbf{B}& \cdots & a_{n_a m_a} \mathbf{B} \end{array}\right]. \] The Kronecker product has some nice properties that facilitate matrix representations. For example, if \(\mathbf{A}\) is \(n_a \times n_a\) and \(\mathbf{B}\) is \(n_b \times n_b\), the inverse and determinants can be expressed in terms of the individual matrices: \[\begin{align*} (\mathbf{A}\otimes \mathbf{B})^{-1} &= \mathbf{A}^{-1} \otimes \mathbf{B}^{-1},\\ |\mathbf{A}\otimes \mathbf{B}| &= |\mathbf{A}|^{n_b} \; |\mathbf{B}|^{n_a}. \end{align*}\]

In the context of spatio-temporal processes, Kronecker products are useful in at least two ways. First, they provide a convenient way to represent spatio-temporal covariance matrices for processes. That is, consider \(\{Y(\mathbf{s}_i;t_j): i=1,\ldots,m;\ j=1,\ldots,T\}\) and define \(\mathbf{C}_y^{(s)}\) to be the \(m \times m\) matrix of purely spatial covariances and \(\mathbf{C}_y^{(t)}\) to be the \(T \times T\) matrix of purely temporal covariances. Then the \(mT \times mT\) spatio-temporal covariance matrix can be written as, \(\mathbf{C}_y = \mathbf{C}_y^{(t)} \otimes \mathbf{C}_y^{(s)}\) if the process is . Although this may not be realistic for many processes, it is advantageous because of the inverse property, \(\mathbf{C}_y^{-1} = (\mathbf{C}_y^{(t)})^{-1} \otimes (\mathbf{C}_y^{(s)})^{-1}\); see Section 4.2.1.

The second way that s are useful for spatio-temporal modeling is for forming spatio-temporal , which we discuss in Section 4.4. In particular, if we construct an \(m \times n_{\alpha,s}\) matrix \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\) by evaluating \(n_{\alpha,s}\) spatial basis functions at \(m\) spatial locations, and a \(T \times n_{\alpha,t}\) matrix \(\boldsymbol{\Psi}\) by evaluating \(n_{\alpha,t}\) temporal basis functions at \(T\) temporal locations, then the matrix constructed from spatio-temporal basis functions formed through the tensor product of the spatial and temporal basis functions and evaluated at all combinations of spatial and temporal locations is given by the \(m T \times n_{\alpha,s} n_{\alpha,t}\) matrix \(\mathbf{B}= \boldsymbol{\Psi}\otimes \boldsymbol{\Phi}\). Basis functions can be used to construct spatio-temporal covariance functions. Note that using a set of basis functions constructed through the yields a class of spatio-temporal covariance functions that are in general not separable.

Sums-and-Products Formulation

There is a useful result in mathematics that states that, as well as the product, the sum of two non-negative-definite functions is non-negative-definite. This allows us to construct valid spatio-temporal covariance functions as the product and/or sum of valid covariance functions. For example,

\[ c(\mathbf{h};\tau) \equiv p \; c_1^{(s)}(\mathbf{h}) \cdot c_1^{(t)}(\tau) + q \; c_2^{(s)}(\mathbf{h}) + r \; c_2^{(t)}(\tau) \tag{4.12}\]

is a valid spatio-temporal covariance function when \(p > 0\), \(q \ge 0\), \(r \ge 0\); \(c_1^{(s)}(\mathbf{h})\) and \(c_2^{(s)}(\mathbf{h})\) are valid spatial covariance functions; and \(c_1^{(t)}(\tau)\) and \(c_2^{(t)}(\tau)\) are valid temporal covariance functions. Of course, Equation 4.12 can be extended to include the sum of many terms and the result is non-negative definite if each component covariance function is non-negative-definite.

The sums-and-products formulation above points to connections between separable covariance functions and other special cases. For example, consider the fully symmetric spatio-temporal covariance functions: a spatio-temporal random process \(\{Y(\mathbf{s};t)\}\) is said to have a fully symmetric spatio-temporal covariance function if, for all spatial locations \(\mathbf{s}, \mathbf{s}'\) in the spatial domain of interest and time points \(t, t'\) in the temporal domain of interest, we can write

\[ \textrm{cov}(Y(\mathbf{s};t),Y(\mathbf{s}';t')) = \textrm{cov}(Y(\mathbf{s};t'),Y(\mathbf{s}';t)). \]

Using such covariances to model spatio-temporal dependence is not always reasonable for real-world processes. For example, is it reasonable that the covariance between yesterday’s temperature in London and today’s temperature in Paris is the same as that between yesterday’s temperature in Paris and today’s temperature in London? Such a relationship might be appropriate under certain meteorological conditions, but not in general (imagine a weather system moving from northwest to southeast across Europe). So, for scientific reasons or as a result of an exploratory data analysis, the fully symmetric covariance function may not be an appropriate choice.

Now, note that the covariance given by Equation 4.12 is an example of a fully symmetric covariance, but it is only separable if \(q=r=0\). In general, separable covariance functions are always fully symmetric, while the converse is not true.

Construction via a Spectral Representation

An important example of the construction approach to spatio-temporal covariance function development was given by Cressie & Huang (1999). They were able to cast the problem in the spectral domain so that one only needs to choose a one-dimensional positive-definite function of time lag in order to obtain a class of valid non-separable spatio-temporal covariance functions. In their Example 1, they construct the stationary spatio-temporal covariance function,

\[ c(\mathbf{h};\tau) = \sigma^2 \exp\{-b^2 ||\mathbf{h}||^2/(a^2 \tau^2 + 1)\}/(a^2 \tau^2 + 1)^{d/2}, \tag{4.13}\]

where \(\sigma^2 =c({\mathbf{0}};0)\), \(d\) corresponds to the spatial dimension (often \(d=2\)), and \(a \ge 0\) and \(b \ge 0\) are scale parameters in space and time, respectively. There are other classes of such spatio-temporal models, and this has been an active area of research in the past few decades (see the overview in Montero et al., 2015).

In this book we limit our focus to gstat when doing S-T kriging. However, there are numerous other packages in R that could be used. Among these CompRandFld and RandomFields are worth noting because of the large selection of non-separable spatio-temporal covariance functions they make available to the user.

Stochastic Partial Differential Equation (SPDE) Approach

The SPDE approach to deriving spatio-temporal covariance functions was originally inspired by statistical physics, where physical equations forced by random processes that describe advective, diffusive, and decay behavior were used to describe the second moments of macro-scale processes, at least in principle. A famous example of this approach in spatial statistics resulted in the ubiquitous Matérn spatial covariance function, which was originally derived as the solution to a fractional stochastic diffusion equation and has been extended by several authors (e.g., Montero et al., 2015).

Although such an approach can suggest non-separable spatio-temporal covariance functions, only a few special (simple) cases lead to closed-form functions Cressie & Wikle (2011). Perhaps more importantly, although these models appear to have a physical basis through the SPDE, macro-scale real-world processes of interest are seldom this simple (e.g., linear and stationary in space and/or time). That is, the spatio-temporal covariance functions that can be obtained in closed form from SPDEs are seldom directly appropriate models for physical processes (but may still provide good fits to data).

4.2.2 Spatio-Temporal Semivariograms

Historically, it has been common in the area of spatial statistics known as geostatistics to consider dependence through the variogram. In the context of a spatio-temporal random process \(\{Y(\mathbf{s};t)\}\), the spatio-temporal variogram is defined as

\[ \textrm{var}(Y(\mathbf{s};t) - Y(\mathbf{s}';t')) \equiv 2 \gamma(\mathbf{s},\mathbf{s}';t,t'), \tag{4.14}\]

where \(\gamma( \cdot)\) is called the (see Note 2.1). The stationary version of the spatio-temporal variogram is denoted by \(2 \gamma(\mathbf{h};\tau)\), where \(\mathbf{h}= \mathbf{s}' - \mathbf{s}\) and \(\tau = t' - t\), analogous to the stationary-covariance representation given previously. The underlying process \(Y\) is considered to be intrinsically stationary if it has a constant expectation and a stationary variogram. When the process is second-order stationary (second-order stationarity is a stronger restriction than intrinsic stationarity), there is a useful and simple relationship between the spatio-temporal and the covariance function, namely,

\[ \gamma(\mathbf{h};\tau) = c(\mathbf{0};0) - c(\mathbf{h};\tau). \tag{4.15}\]

Notice that strong spatio-temporal dependence corresponds to small values of the . Thus, contour plots of \(\{\gamma(\mathbf{h};\tau)\}\) in Equation 4.15 start near zero close to the origin \((\mathbf{h};\tau) = (\mathbf{0},0)\), and they rise to a constant value (the “sill”) as both \(\mathbf{h}\) and \(\tau\) move away from the origin.

Although there has been a preference to consider dependence through the variogram in geostatistics, this has not been the case in more mainstream spatio-temporal statistical analyses. The primary reason for this is that most real-world processes are best characterized in the context of local second-order stationarity. The difference between intrinsic stationarity and second-order stationarity is most appreciated when the lags \(\mathbf{h}\) and \(\tau\) are large. If only local stationarity is expected and modeled, the extra generality given by the variogram is not needed. Still, the empirical semivariogram offers a useful way to summarize the spatio-temporal dependence in the data and to fit a spatio-temporal covariance function.

On a theoretical level, the stationary variogram allows S-T for a larger class of processes (i.e., intrinsically stationary processes) than the second-order stationary processes. A price to pay for this extra generality is the extreme caution needed when using the variogram to find optimal coefficients. Cressie & Wikle (2011, p. 148) point out that the universal- weights may not sum to 1 and, in situations where they do not, the resulting variogram-based predictor will not be optimal. However, when using the covariance-based predictor, there are no such issues and it is always optimal.

In addition, on a more practical level, most spatio-temporal analyses consider models that are specified from a likelihood perspective or a perspective, where covariance matrices are needed. The variogram by itself does not specify the covariance matrix, since one also needs to model the variance function \(\sigma^2(\mathbf{s};t) \equiv \textrm{var}(Y(\mathbf{s};t))\), which is usually impractical unless it is stationary and does not depend on \(\mathbf{s}\) and \(t\). Some software packages that perform S-T , such as gstat, fit variogram functions to data, mainly for historical reasons and because of the implicit assumption in Equation 4.14 that a constant mean need not be assumed when estimating the variogram. (This is generally a good thing because the constant mean assumption is tenuous in practice, since the mean for real-world processes typically depends on exogenous covariates that vary with space and time.)

4.2.3 Gaussian Spatio-Temporal Model Estimation

The spatio-temporal covariance and variogram functions presented above depend on unknown parameters. These are almost never known in practice and must be estimated from the data. There is a history in spatial statistics of fitting covariance functions (or semivariograms) directly to the empirical estimates – for example, by using a least squares or weighted least squares approach (see Cressie (1993) for an overview). However, in the spatio-temporal context we prefer to consider fully parameterized covariance models and infer the parameters through likelihood-based methods or through fully methods. This follows closely the approaches in mixed-linear-model parameter estimation; for an overview, see McCulloch & Searle (2001). We briefly describe the likelihood-based approach and the approach below.

Likelihood Estimation

Given the data model Equation 4.3, note that \(\mathbf{C}_z = \mathbf{C}_y + \mathbf{C}_\epsilon\). Then, in obvious notation, \(\mathbf{C}_z\) depends on parameters \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\equiv \{\boldsymbol{\theta}_y,\boldsymbol{\theta}_\epsilon\}\) for the covariance functions of the hidden process \(Y\) and the measurement-error process \(\epsilon\), respectively. The likelihood can then be written as

\[ L(\boldsymbol{\beta},\boldsymbol{\theta}; \mathbf{Z}) \propto |\mathbf{C}_z(\boldsymbol{\theta})|^{-1/2} \exp\left\{-\frac{1}{2}(\mathbf{Z}- \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta})'(\mathbf{C}_z(\boldsymbol{\theta}))^{-1}(\mathbf{Z}- \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta})\right\}, \tag{4.16}\]

and we maximize this with respect to \(\{\boldsymbol{\beta},\boldsymbol{\theta}\}\), thus obtaining the maximum likelihood estimates (MLEs), \(\{\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathrm{mle}}, \widehat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_{\mathrm{mle}}\}\). Because the covariance parameters appear in the matrix inverse and determinant in Equation 4.16, analytical maximization for most parametric covariance models is not possible, but numerical methods can be used. To reduce the number of parameters in this maximization, we often consider “profiling,” where we replace \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) in Equation 4.16 with the generalized least squares estimator, \({\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathrm{gls}} = (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{C}_z(\boldsymbol{\theta})^{-1} \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{C}_z(\boldsymbol{\theta})^{-1} \mathbf{Z}\) (which depends only on \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\)). Then the profile likelihood is just a function of the unknown parameters \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\). Using a numerical optimization method (e.g., Newton–Raphson) to obtain \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_{\mathrm{mle}}\), we then obtain \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathrm{mle}} = (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{C}_z(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_{\mathrm{mle}})^{-1} \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{C}_z(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_{\mathrm{mle}})^{-1} \mathbf{Z}\), which is the MLE of \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\). The parameter estimates \(\{\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathrm{mle}}, \widehat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_{\mathrm{mle}}\}\) are then substituted into the kriging equations above (e.g., Equation 4.8 and Equation 4.10) to obtain the empirical best linear unbiased predictor (EBLUP) and the associated empirical prediction variance.

Maximizing the log-likelihood (i.e., the \(\log\) of Equation 4.16) in R can be done in a number of ways. Among the most popular functions in base R are nlm, which implements a Newton-type algorithm, and optim, which contains a number of general-purpose routines, some of which are gradient-based. When a simple covariance function is used, the gradient can be found analytically, and gradient information may then be used to facilitate optimization. Many of the parameters in our models (such as the variance or dependence-scale parameters) need to be positive to ensure positive-definite covariance matrices. This can be easily achieved by finding the MLEs of the log of the parameters, instead of the parameters themselves. Then the MLE of the parameter on the original scale is obtained by exponentiating the MLE on the log scale. In this case, one typically uses the delta method to obtain the variance of the transformed parameter estimates (see, for example, Kendall & Stuart, 1969).

As described in Note 4.2, restricted maximum likelihood (REML) considers the likelihood of a linear transformation of the data vector such that the errors are orthogonal to the \(\mathbf{X}\)s that make up the mean function. Numerical maximization of the associated likelihood, which is only a function of the parameters \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) (i.e., not of \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\)), gives \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_{\mathrm{reml}}\). These estimates are substituted into Equation 4.9, the GLS formula for \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\), to obtain \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathrm{reml}}\) as well as the kriging equations Equation 4.8 and Equation 4.10.

Both the MLE and REML approaches have the advantage that they are based on the “likelihood principle” and, assuming that the Gaussian distributional assumptions are correct, they have desirable properties such as sufficiency, invariance, consistency, efficiency, and asymptotic normality. In mixed-effects models and in spatial statistics, REML is usually preferred over MLE for estimation of covariance parameters because REML typically has less bias in small samples (see, for example, the overview in Wu et al., 2001).

Consider a contrast matrix \(\mathbf{K}\) such that \(E(\mathbf{K}\mathbf{Z}) = \mathbf{0}\). For example, let \(\mathbf{K}\) be an \((m - p ) \times m\) matrix orthogonal to the column space of the \(m \times p\) design matrix \(\mathbf{X}\). That is, let \(\mathbf{K}\) correspond to the \(m - p\) linearly independent rows of \((\mathbf{I}- \mathbf{X}(\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}')\). Because \(\mathbf{K}\mathbf{X}= \mathbf{0}\), it follows that \(E(\mathbf{K}\mathbf{Z}) = \mathbf{K}\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta}= \mathbf{0}\), and \(\textrm{var}(\mathbf{K}\mathbf{Z}) = \mathbf{K}\mathbf{C}_z(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \mathbf{K}'\). In this case, the likelihood based on \(\mathbf{K}\mathbf{Z}\) is not a function of the mean parameters \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) and is given by

\[ L_{\mathrm{reml}}(\boldsymbol{\theta};\mathbf{Z}) \propto |\mathbf{K}\mathbf{C}_z(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \mathbf{K}'|^{-1/2} \exp\left\{-\frac{1}{2}(\mathbf{K}\mathbf{Z})'(\mathbf{K}\mathbf{C}_z(\boldsymbol{\theta}) \mathbf{K}')^{-1}(\mathbf{K}\mathbf{Z}) \right\}. \tag{4.17}\]

Then Equation 4.17 is maximized numerically to obtain \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_{\mathrm{reml}}\). Note that parameter estimation and statistical inference with REML do not depend on the specific choice of \(\mathbf{K}\), so long as it is a contrast matrix that leads to \(E(\mathbf{K}\mathbf{Z}) = \mathbf{0}\) (Patterson & Thompson, 1971). One can then use these estimates in a GLS estimate of \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\): \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\beta}}_{\mathrm{reml}} \equiv (\mathbf{X}' \mathbf{C}_z(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_{\mathrm{reml}})^{-1} \mathbf{X})^{-1} \mathbf{X}' \mathbf{C}_z(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}_{\mathrm{reml}})^{-1} \mathbf{Z}\).

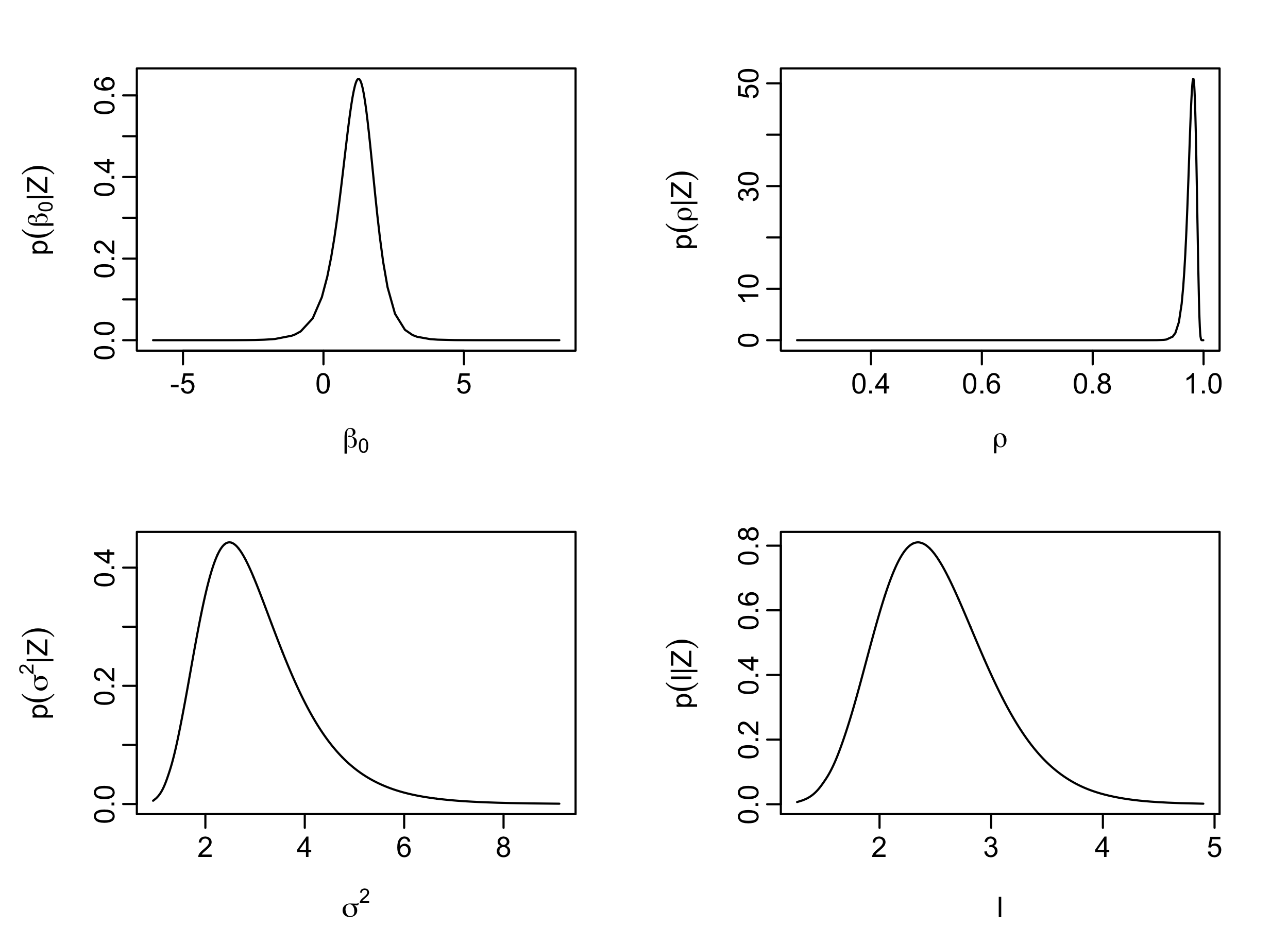

Bayesian Inference

Instead of treating \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) as fixed, unknown, and to be estimated (e.g., from the likelihood), prior distributions \([\boldsymbol{\beta}]\) and \([\boldsymbol{\theta}]\) (often assumed independent) could be posited for the mean parameters \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) and the covariance parameters \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\), respectively. Typical choices for \([\boldsymbol{\theta}]\) do not admit closed-form posterior distributions for \([Y(\mathbf{s}_0) | \mathbf{Z}]\), which means that the predictor \(E(Y(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0) | \mathbf{Z})\) and the associated uncertainty, \(\textrm{var}(Y(\mathbf{s}_0;t_0) | \mathbf{Z})\), are not available in closed form and must be obtained through numerical evaluation of the posterior distribution (for more details, see Section 4.5.2 below; Cressie & Wikle (2011); Banerjee et al. (2015)).

Example: S-T Kriging

Consider the maximum-temperature observations in the NOAA data set Tmax. The empirical covariogram of these data is shown in the top left panel of Figure 4.4. Consider two spatio-temporal covariance functions fitted to the residuals from a model with a regression component that includes an intercept and latitude as a covariate. The first of these covariance functions is given by an isotropic and stationary separable model of the form

\[ c^{(\mathrm{sep})}(\| \mathbf{h}\| ; | \tau|) \equiv c^{(s)}(\| \mathbf{h}\|) \cdot c^{(t)}(|\tau|), \tag{4.18}\]

in which we let both covariance functions, \(c^{(s)}(\cdot)\) and \(c^{(t)}(\cdot)\), take the form

\[ c^{(\cdot)}(h) = b_1\exp(-\phi h) + b_2I(h=0), \tag{4.19}\]

where \(\phi\), \(b_1\), and \(b_2\) are parameters that are different for \(c^{(s)}(\cdot)\) and \(c^{(t)}(\cdot)\) and need to be estimated; and \(I(\cdot)\) is the indicator function that is used to represent the so-called nugget effect, made up of the measurement-error variance plus the micro-scale variation. The fitted model is shown in the bottom left panel of Figure 4.4.

The second model we fit is a non-separable spatio-temporal covariance function, in which the temporal lag is scaled to account for the different nature of space and time. This model is given by

\[ c^{(\mathrm{st})}(\| \mathbf{v}_a \|) \equiv b_1\exp(-\phi \| \mathbf{v}_a \|) + b_2I(\| \mathbf{v}_a \| = 0), \tag{4.20}\]

where \(\mathbf{v}_a \equiv (\mathbf{h}',a \tau)'\), and recall that \(||\mathbf{v}_a|| = (\mathbf{h}' \mathbf{h}+ a^2 \tau^2)^{1/2}\). Here, \(a\) is the scaling factor used for generating the space-time anisotropy. The fitted model is shown in the bottom right panel of Figure 4.4.

The non-separable spatio-temporal covariance function (Equation 4.20) allows for space-time anisotropy, but it is otherwise relatively inflexible. It only contains one parameter (\(a\)) to account for the different scaling needed for space and time, one parameter (\(\phi\)) for the length scale, and two parameters to specify the variance (the nugget effect, \(b_2\), and the variance of the smooth component, \(b_1\)). Thus, Equation 4.20 has a total of four parameters, in contrast to the six parameters in Equation 4.18. This results in a relatively poor fit to the Tmax data from the NOAA data set. In this case, the separable model is able to provide a better reconstruction of the empirical covariance function despite its lack of space-time interaction, which is not surprising given that the fitted separable covariance function (Figure 4.4, top right) is visually similar to the empirical spatio-temporal covariance function (Figure 4.4, top left). We note that although the separable model fits better in this case, it is still a rather unrealistic model for most processes of interest.

4.3 Random-Effects Parameterizations

As discussed previously, it can be difficult to specify realistic valid spatio-temporal covariance functions and to work with large spatio-temporal covariance matrices (e.g., \(\mathbf{C}_z\)) in situations with large numbers of prediction or observation locations. One way to mitigate these problems is to take advantage of conditional specifications that the hierarchical modeling framework allows.

We can consider classical linear mixed models from either a conditional perspective, where we condition the response on the random effects, or from a marginal perspective, where the random effects have been averaged (integrated) out (see Note 4.3), and it is this marginal distribution that is modeled. We digress briefly from the spatio-temporal context to illustrate the conditional versus marginal approach in a simple longitudinal-data-analysis setting. Longitudinal data are collected over time, often in a clinical trial where the response to drug treatments and controls is measured on the same subjects at different follow-up times. Here, one might allow there to be subject-specific intercepts or slopes corresponding to the treatment effect over time.

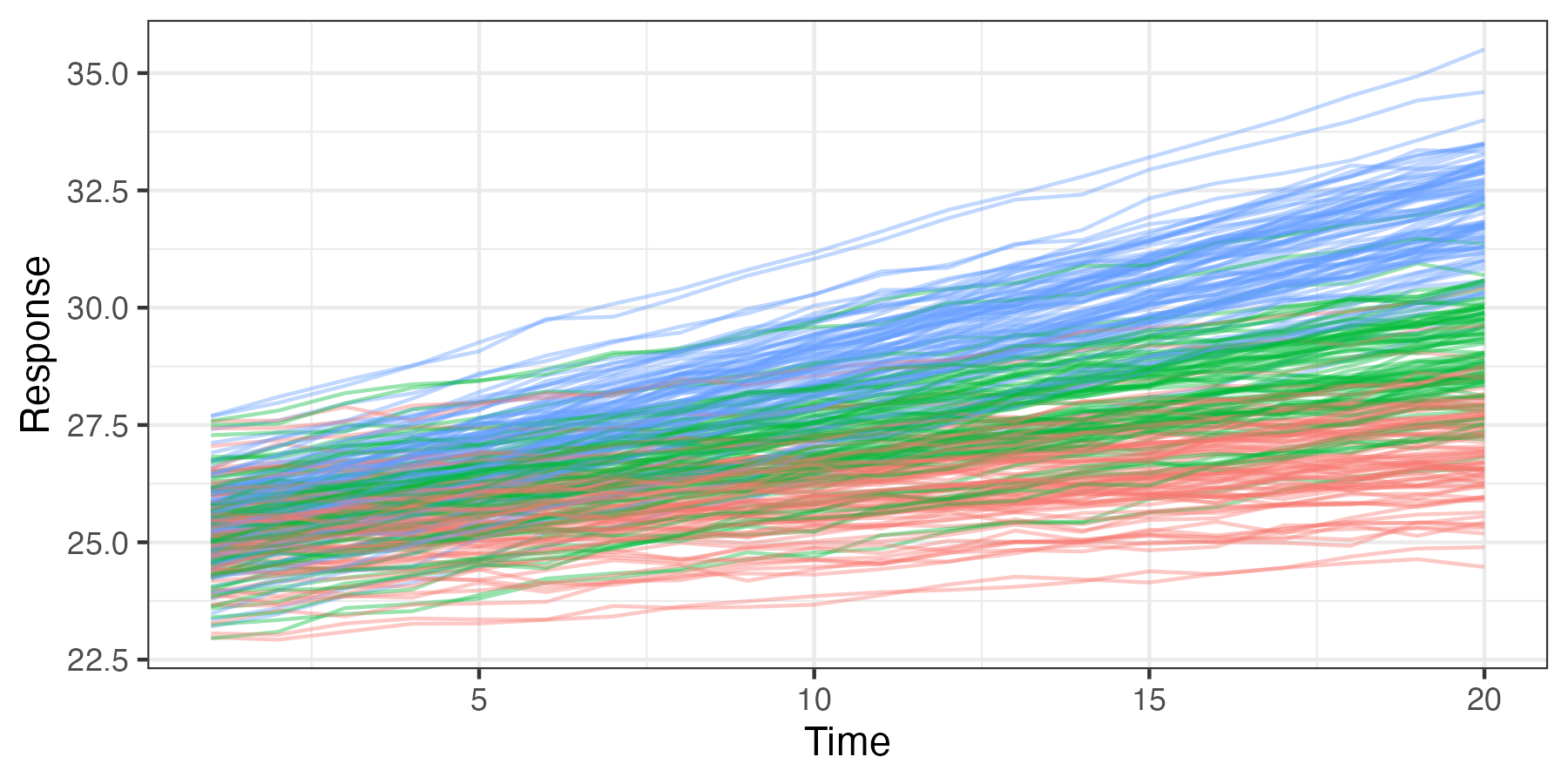

Figure 4.5 shows simulated data for a longitudinal study in which 90 individuals are assigned randomly to three treatment groups (control, treatment 1, and treatment 2), 30 per group. Their responses are then plotted through time (20 time points). In each case, the response is generally linear with time, with individual-specific random intercepts and slopes. These responses can be modeled in terms of a linear mixed model, with fixed effects corresponding to the treatment (control, treatment 1, and treatment 2), individual random effects for the slope and intercept, and a random effect for the error. The random effects correspond to a situation where individuals have somewhat different baseline responses (intercept), and their response with time to the treatment is also subject to individual variation (slope).

For the simulated data shown in Figure 4.5, we might consider a longitudinal model such as Verbeke & Molenberghs (2009), Section 3.3:

\[ Z_{ij} = \left\{ \begin{array}{ll} (\beta_0 + \alpha_{0i}) + (\beta_1 + \alpha_{1i}) t_{j} + \epsilon_{ij}, & \text{if the subject receives the control}, \\ (\beta_0 + \alpha_{0i}) + (\beta_2 + \alpha_{1i}) t_{j} + \epsilon_{ij}, & \text{if the subject receives treatment 1}, \\ (\beta_0 + \alpha_{0i}) + (\beta_3 + \alpha_{1i}) t_{j} + \epsilon_{ij}, & \text{if the subject receives treatment 2}, \end{array} \right. \]

where \(Z_{ij}\) is the response for the \(i\)th subject (\(i=1,\ldots,n=90\)) at time \(j=1,\ldots,T=20\); \(\beta_0\) is an overall fixed intercept; \(\beta_1, \beta_2, \beta_3\) are fixed time-trend effects; and \(\alpha_{0i} \sim \text{iid} \, \text{Gau}(0,\sigma^2_1)\) and \(\alpha_{1i} \sim \text{iid} \, \text{Gau}(0,\sigma^2_2)\) are individual-specific random intercept and slope effects, respectively. We can write this model in the classical linear mixed-model notation as

\[ \mathbf{Z}_i = \mathbf{X}_i \boldsymbol{\beta}+ \boldsymbol{\Phi}\boldsymbol{\alpha}_i + \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_i, \]

where \(\mathbf{Z}_i\) is a \(20\)-dimensional vector of responses for the \(i\)th individual; \(\mathbf{X}_i\) is a \(20 \times 4\) matrix consisting of a column vector of \(1\)s (intercept) and three columns indicating the treatment group of the \(i\)th individual; \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) is a four-dimensional vector of fixed effects; \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\) is a \(20 \times 2\) matrix with a vector of \(1\)s in the first column and the second column consists of the vector of times, \((1,2,\ldots,20)'\); the associated random-effect vector is \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}_i \equiv (\alpha_{0i},\alpha_{1i})' \sim \text{Gau}(\mathbf{0},\mathbf{C}_\alpha)\), where \(\mathbf{C}_\alpha = \text{diag}(\sigma^2_1, \sigma^2_2)\); and \(\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_i \sim \text{Gau}(\mathbf{0},\sigma^2_\epsilon \mathbf{I})\) is a \(20\)-dimensional error vector. We assume that the elements of \(\{\boldsymbol{\alpha}_i\}\) and \(\{\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}_i\}\) are all mutually independent.

Because the variation in the individuals’ intercepts and slopes is specified by random effects, this formulation allows one to consider inference at the subject (individual) level (e.g., predictions of an individual’s true values). However, if interest is in the fixed treatment effects \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\), one might consider the marginal distribution of the responses in which these individual random effects have been removed through averaging (integration). Responses that share common random effects exhibit marginal dependence through the marginal covariance matrix, and so the inference on the fixed effects (e.g., via generalized least squares) then accounts for this more complicated marginal dependence. For the example presented here, one can show that the marginal covariance for an individual’s response at time \(t_j\) and \(t_k\) is given by \(\mbox{cov}(Z_{ij},Z_{ik}) = \sigma^2_1 + t_j t_k \sigma^2_2 + \sigma^2_\epsilon I(j = k)\), which says that the marginal variance is time-varying, whereas the conditional covariance (conditioned on \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}\)) is simply \(\sigma^2_\epsilon I(j = k)\).

In the context of spatial or spatio-temporal modeling, the same considerations as for the classical linear mixed-effects model apply. That is, we can also write the process of interest conditional on random effects, where the random effects might be spatial, temporal, or spatio-temporal. Why is this important? As we show in the next section, it allows us to build spatio-temporal dependence conditionally, in such a way that the implied marginal spatio-temporal covariance function is always valid, and it provides some computational advantages.

Consider the conditional representation of a classic general linear mixed-effects model Laird & Ware (1982) for response vector \(\mathbf{Z}\) and fixed and random effects vectors, \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}\), respectively. Specifically, consider

\[ \mathbf{Z}| \boldsymbol{\alpha}\sim Gau(\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta}+ \boldsymbol{\Phi}\boldsymbol{\alpha}, \mathbf{C}_\epsilon), \tag{4.21}\]

\[ \boldsymbol{\alpha}\sim Gau({\mathbf{0}}, \mathbf{C}_\alpha), \]

where \(\mathbf{X}\) and \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\) are assumed to be known matrices, and \(\mathbf{C}_\epsilon\) and \(\mathbf{C}_\alpha\) are known covariance matrices. The marginal distribution of \(\mathbf{Z}\) is then given by integrating out the random effects:

\[ [\mathbf{Z}] = \int [\mathbf{Z}\; | \; \boldsymbol{\alpha}][\boldsymbol{\alpha}] \textrm{d}\boldsymbol{\alpha}. \tag{4.22}\]

Note that dependence on \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\), which recall are the covariance parameters in \(\mathbf{C}_z\) and \(\mathbf{C}_\alpha\), has been suppressed in Equation 4.22, although the (implicit) presence of \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) can be seen in Equation 4.23–Equation 4.26 below. We can obtain this distribution by making use of iterated conditional expectation and variance formulas. In particular, note that we can write the model associated with Equation 4.21 as

\[ \mathbf{Z}= \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta}+ \boldsymbol{\Phi}\boldsymbol{\alpha}+ \boldsymbol{\varepsilon}, \quad\boldsymbol{\varepsilon}\sim Gau({\mathbf{0}}, \mathbf{C}_\epsilon), \tag{4.23}\]

and then

\[ E(\mathbf{Z}) = E_{\alpha}\{E(\mathbf{Z}| \boldsymbol{\alpha})\} = E_{\alpha}\{\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta}+ \boldsymbol{\Phi}\boldsymbol{\alpha}\} = \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta}, \tag{4.24}\]

\[ \textrm{var}(\mathbf{Z}) = \textrm{var}_{\alpha}\{E(\mathbf{Z}| \boldsymbol{\alpha})\} + E_{\alpha}\{\textrm{var}(\mathbf{Z}| \boldsymbol{\alpha})\} = \boldsymbol{\Phi}\mathbf{C}_\alpha \boldsymbol{\Phi}' + \mathbf{C}_\epsilon. \tag{4.25}\]

Then, since Equation 4.23 shows that \(\mathbf{Z}\) is a linear combination of normally distributed random variables, it is also normally distributed and the marginal distribution is given by

\[ \mathbf{Z}\; \sim \; Gau(\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta}, \boldsymbol{\Phi}\mathbf{C}_\alpha \boldsymbol{\Phi}' + \mathbf{C}_\epsilon). \tag{4.26}\]

Thus, we can see that the integration over the common random effects \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}\) in Equation 4.22 induces a more complicated error covariance structure in the marginal distribution (i.e., compare the marginal covariance matrix, \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\mathbf{C}_\alpha \boldsymbol{\Phi}' + \mathbf{C}_\epsilon\), to the conditional covariance matrix, \(\mathbf{C}_\epsilon\)). This idea of conditioning on random effects and inducing dependence through integration is fundamentally important to hierarchical statistical modeling. That is, it is typically easier to model means than it is to model covariances, and so we put our modeling effort into the conditional mean and then let the integration induce the more complicated marginal dependence rather than specifying it directly.

4.4 Basis-Function Representations

By themselves, the conditional specifications discussed in Section 4.3 are often not enough to help us deal with the problem of specifying realistic spatio-temporal covariance structures and deal with the “curse of dimensionality,” which is endemic in spatio-temporal statistics. We also need to pay particular attention to our choice of \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\), and we often do this through basis-function expansions (recall that we introduced basis functions in Chapter 1 and in more detail in Chapter 3).

Basis functions, like covariates, can be nonlinear functions of \((\mathbf{s};t)\); however, the expansion is a linear function of the basis functions’ coefficients. We assume that these coefficients are the objects of inference in a statistical additive model. If the coefficients are fixed but unknown and to be estimated, then we have a regression model and the basis functions act as covariates (see, for example, Section 3.2). If the coefficients are random, then we have a random-effects model (or, if covariates are also present, a mixed-effects model) and we can perform inference on the moments of those random effects. More importantly, as we have shown in Section 4.3, this framework allows us to build complexity through marginalization. This often simplifies the model specification, particularly if we consider the random effects to be associated with spatial, temporal, or spatio-temporal . In the following subsections, we consider spatio-temporal models that involve these three types of basis functions.

4.4.1 Random Effects with Spatio-Temporal Basis Functions

Assuming the same data model (Equation 4.3) as above, we rewrite the process model (Equation 4.2) in terms of fixed and random effects, \(\boldsymbol{\beta}\) and \(\{\alpha_i: i=1,\ldots,n_\alpha\}\), respectively:

\[ Y(\mathbf{s};t) = \mathbf{x}(\mathbf{s};t)'\boldsymbol{\beta}+ \eta(\mathbf{s};t) \; = \; \mathbf{x}(\mathbf{s};t)'\boldsymbol{\beta}+ \sum_{i=1}^{n_\alpha} \phi_{i}(\mathbf{s};t) \alpha_i + \nu(\mathbf{s};t), \tag{4.27}\]

where \(\{\phi_{i}(\mathbf{s};t): i=1,\ldots,n_\alpha \}\) are specified spatio-temporal corresponding to location \((\mathbf{s};t)\), \(\{\alpha_i\}\) are random effects, and \(\nu(\mathbf{s};t)\) is sometimes needed to represent small-scale spatio-temporal random effects not captured by the basis functions. So, in Equation 4.27 we are just decomposing the spatio-temporal random process, \(\eta(\mathbf{s};t)\), into a linear combination of random effects and a “residual” error term.

Let \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}\sim Gau({\mathbf{0}},\mathbf{C}_\alpha)\), where \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}\equiv (\alpha_1,\ldots,\alpha_{n_\alpha})'\). Suppose we are interested in making inference on the process \(Y\) at \(n_y\) spatio-temporal locations, which we denote by the \(n_y\)-dimensional vector \(\mathbf{Y}\). The process model then becomes

\[ \mathbf{Y}= \mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta}+ \boldsymbol{\Phi}\boldsymbol{\alpha}+ \boldsymbol{\nu}, \tag{4.28}\]

where the \(i\)th column of the \(n_y \times n_\alpha\) matrix \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\) corresponds to the \(i\)th basis function, \(\phi_{i}(\cdot;\cdot)\), at all of the \(n_y\) spatio-temporal locations, and in the same order as that used to construct \(\mathbf{Y}\). The vector \(\boldsymbol{\nu}\) also corresponds to the spatio-temporal ordering given in \(\mathbf{Y}\), and \(\boldsymbol{\nu}\sim Gau({\mathbf{0}},\mathbf{C}_\nu)\). In this case, one can see (Note 4.3) that the marginal distribution of \(\mathbf{Y}\) is given by \(\mathbf{Y}\sim Gau(\mathbf{X}\boldsymbol{\beta}, \boldsymbol{\Phi}\mathbf{C}_\alpha \boldsymbol{\Phi}' + \mathbf{C}_\nu )\), so that \(\mathbf{C}_y = \boldsymbol{\Phi}\mathbf{C}_\alpha \boldsymbol{\Phi}' + \mathbf{C}_\nu\). Now the vector of covariance parameters \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\) is augmented to include parameters in \(\mathbf{C}_\nu\). The spatio-temporal dependence is accounted for by the spatio-temporal basis functions, \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\), and in general this could accommodate non-separable dependence. A benefit of this approach is that the spatio-temporal modeling effort focuses on the fixed number \(n_\alpha\) of random effects. In this case, note that the random effects \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}\) are not indexed by space and time, so it should be easier to specify a model for them. For example, we can specify a covariance matrix to describe their dependence, which is easier than specifying a covariance function.

In situations where \(n_\alpha \ll n_y\) (i.e., a low-rank representation), an additional benefit comes from being able to perform matrix inverses in terms of \(n_\alpha\)-dimensional matrices (through well-known matrix-algebra relationships). Specifically, under model Equation 4.28 we note that we can write \(\mathbf{C}_z = \boldsymbol{\Phi}\mathbf{C}_\alpha \boldsymbol{\Phi}' + \mathbf{V}\), where we define \(\mathbf{V}\equiv \mathbf{C}_\nu + \mathbf{C}_\epsilon\). Then, using the well-known Sherman–Morrison–Woodbury matrix identities [e.g., available at https://doi.org/10.1007/978-1-4757-2085-3] (Searle, 1982), we can write

\[ \mathbf{C}_z^{-1} = \mathbf{V}^{-1} - \mathbf{V}^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Phi}(\boldsymbol{\Phi}' \mathbf{V}^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Phi}+ \mathbf{C}_\alpha^{-1})^{-1} \boldsymbol{\Phi}' \mathbf{V}^{-1}. \]

Importantly, if \(\mathbf{V}^{-1}\) has simple structure (e.g., is sparse or diagonal) and \(n_\alpha \ll n_y\), then this inverse is easy to calculate because it is a function of a simple high-dimensional matrix \(\mathbf{V}^{-1}\) and a low-dimensional matrix inverse \(\mathbf{C}_\alpha^{-1}\).

It is important to note that even in the full-rank (\(n_\alpha = n_y\)) and over-complete (\(n_\alpha > n_y\)) cases there can still be computational benefits through induced sparsity in \(\mathbf{C}_\alpha\) and the use of efficient matrix-multiplication routines that use multiresolution algorithms, orthogonality, and/or sparse precision matrices. In addition, basis-function implementations may assume that \(\boldsymbol{\nu}= {\mathbf{0}}\) and often that \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\) is orthogonal, so that \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\boldsymbol{\Phi}' = \mathbf{I}\); in those cases, one can reduce the computational burden significantly. Finally, we note that specific and methodologies are devised to take advantage of other properties of various matrices (e.g., sparse structure on the random-effects covariance matrix, \(\mathbf{C}_\alpha\), or on the random-effects precision matrix, \(\mathbf{C}_\alpha^{-1}\)).

Sparse matrices can be used in R using definitions in the packages Matrix or spam. For both these packages, arithmetic operations, decompositions (e.g., the Cholesky decomposition), back-solves and forward-solves, and other important matrix operations, can be done seamlessly using standard R commands. With Matrix, a sparse matrix can be constructed using the function sparseMatrix, while a sparse diagonal matrix can be constructed using the function Diagonal. With the former, the argument symmetric = TRUE can be used to specify a sparse symmetric matrix.

The definition of “basis function” in our spatio-temporal context is pretty liberal; the matrix \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\) in the product \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\boldsymbol{\alpha}\) is a spatio-temporal basis-function matrix so long as its coefficients \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}\) are random and the columns of \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\) are spatio-temporally referenced. One decision associated with fitting model Equation 4.27 concerns the choice of . For spatial processes, the decisions one makes with regard to the choice of are usually not that critical, as there are multiple types of bases that can accommodate the same spatial variability. However, as one starts considering spatio-temporal processes, the choice of can make a difference, especially for the dynamical formulations presented in Chapter 5.

In general, one can use (i) fixed or parameterized basis functions, (ii) local or global , (iii) reduced-rank, complete, or over-complete bases, and (iv) basis functions with expansion coefficients possibly indexed by space, time, or space-time. Further, the choice is affected by the presence and type of residual structure and the distribution of the random effects. Historically, it has been fairly challenging to come up with good spatio-temporal basis functions (for the same reason it has been difficult to come up with truly realistic spatio-temporal covariance functions). One simplification is to consider tensor-product (mentioned in Section 3.2 and Note 4.1), where we define the spatio-temporal basis function as the product of a spatial basis function and a temporal basis function. Note that this does not yield a separable spatio-temporal model, in general. It is also quite common to see spatio-temporal-dependence models for \(Y\), where the statistical dependence comes from spatial-only whose coefficients are temporal stochastic processes (Section 4.4.2).

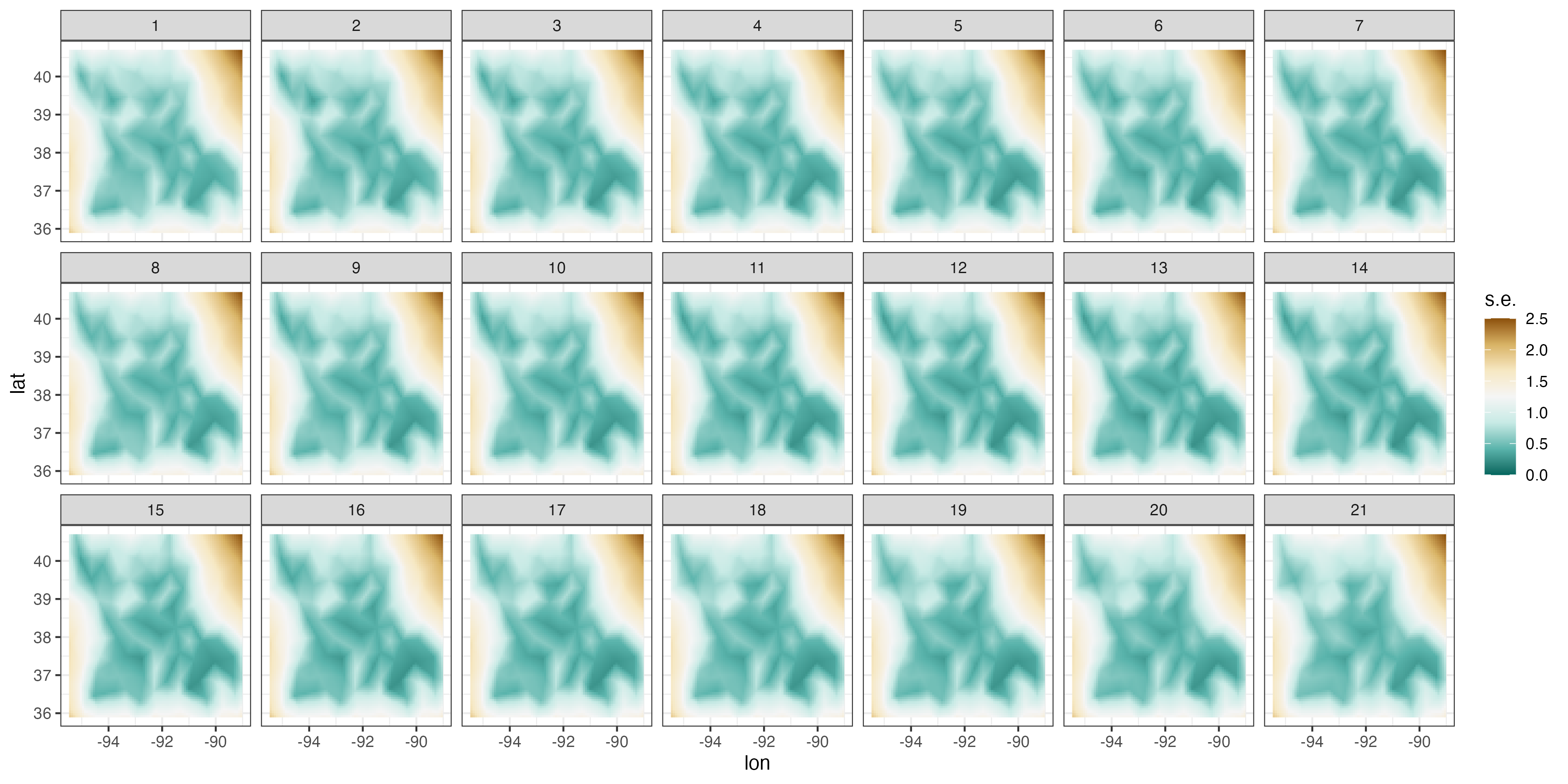

Example: Fixed Rank Kriging

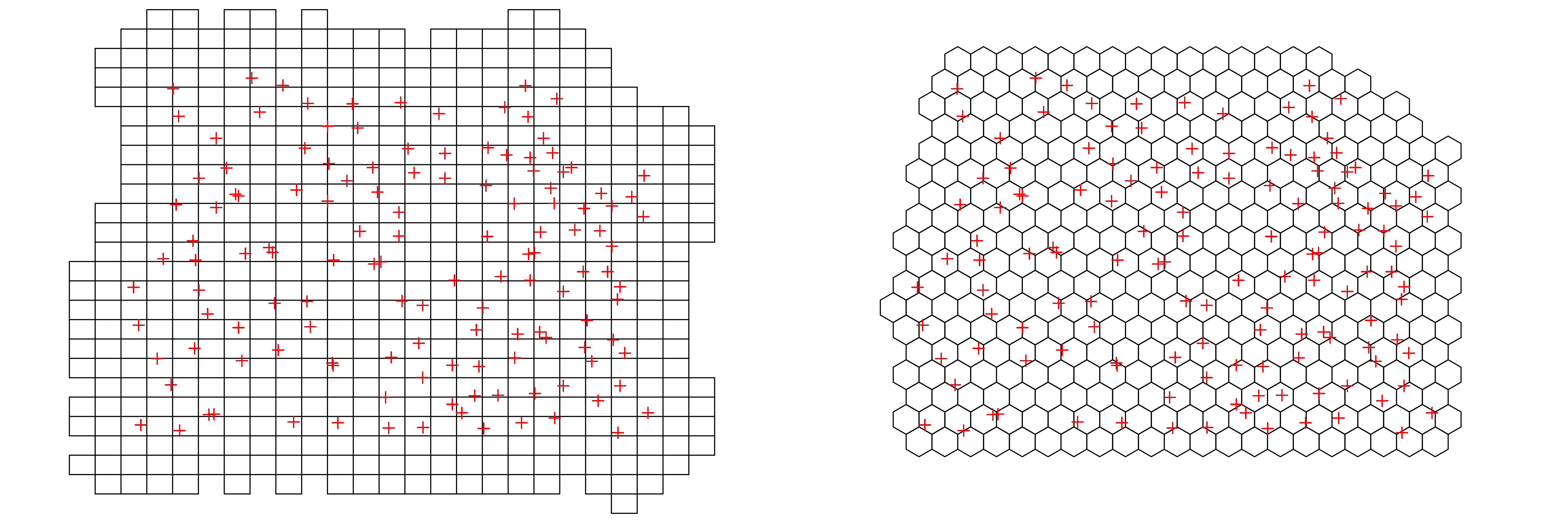

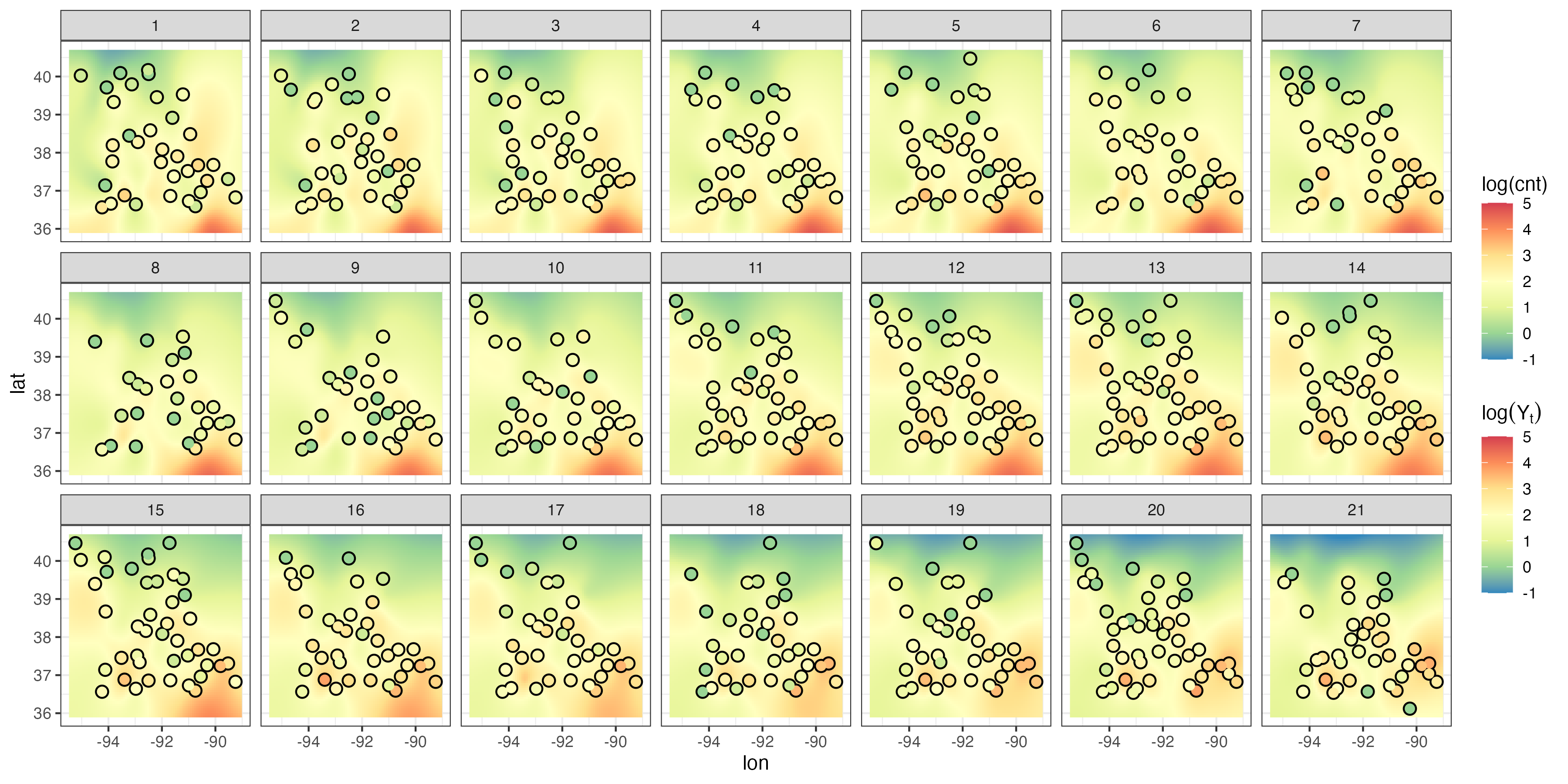

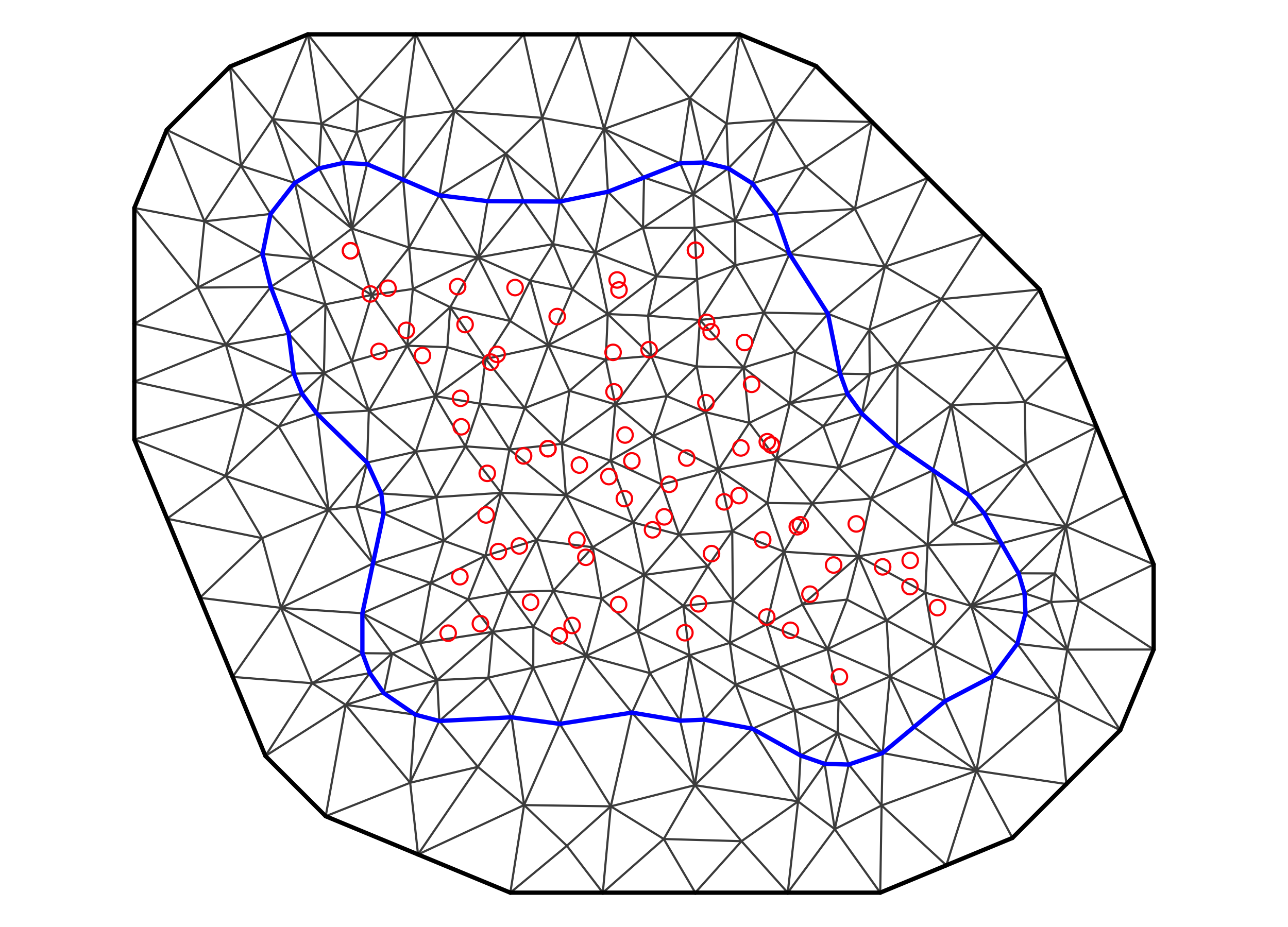

A widely adopted method for rank reduction is fixed rank kriging (FRK), implemented in R through the package FRK. Lab 4.2 demonstrates how FRK can be applied to the maximum temperature (Tmax) in the NOAA data set using \(n_\alpha = 1880\) space-time tensor-product basis functions (see Note 4.1) at two resolutions for \(\{\phi_i(\mathbf{s};t):i=1,\dots,n_\alpha\}\). In particular, bisquare basis functions are used (see Lab 4.2 for details). FRK also considers a fine-scale-variation component \(\boldsymbol{\nu}\) such that \(\mathbf{C}_\nu\) is diagonal. The matrix \(\mathbf{C}_\alpha\) is constructed such that the coefficients \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}\) at each resolution are independent, and such that the covariances between these coefficients within a resolution decay exponentially with the distance between the centers of the basis functions. Parameters are estimated using an EM algorithm for computing maximum likelihood estimates (see Note 4.4).

Figure 4.6 shows the predictions and prediction standard errors obtained using FRK; as is typical for kriging, the computations are made with \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\) substituted in for the unknown covariance parameters \(\boldsymbol{\theta}\). Although the uncertainty in \(\widehat{\boldsymbol{\theta}}\) is not accounted for in this setting, it is typically thought to be a fairly minor component of the variation in the spatio-temporal prediction. The predictions are similar to those obtained using S-T kriging in Figure 4.2 of Section 4.2, but they are also a bit “noisier” because of the assumed uncorrelated fine-scale variation term; see Equation 4.27. The prediction standard errors show similar patterns to those obtained earlier (Figure 4.2), although there are notable differences upon visual examination. This is commonly observed when using reduced-rank methods, and it is particularly evident with very-low-rank implementations (e.g., with EOFs) accompanied with spatially uncorrelated fine-scale variation. In such cases, the prediction-standard-error maps can have prediction standard errors related more to the shapes of the basis functions and less to the prediction location’s proximity to an observation.

Tmax and right: prediction standard errors in degrees Fahrenheit within a square box enclosing the domain of interest for six days (each 5 days apart) spanning the temporal window of the data, 01 July 1993–20 July 2003, using bisquare spatio-temporal and the R package FRK. Data for 14 July 1993 were omitted from the original data set.

In some cases, it can be computationally more efficient to perform maximum likelihood estimation using the expectation-maximization (EM) algorithm rather than through direct optimization of the likelihood function. The basic idea is that one defines complete data to be a combination of actual observations and missing observations. Let \(W\) denote these complete data made up of observations (\(W_{\mathrm{obs}}\)) and “missing” observations (\(W_{\mathrm{mis}}\)), and \(\theta\) represents the unknown parameters in the model, so that the complete-data log-likelihood is given by \(\log(L(\theta | W))\). The basic EM algorithm is given below.

Choose starting values for the parameter, \(\hat{\theta}^{(0)}\)

repeat \(i=1,2,\ldots\)

- E-Step: Obtain \(Q(\theta | \hat{\theta}^{(i-1)}) = E\{\log(L(\theta \mid W)) \mid W_{\mathrm{obs}}, \hat{\theta}^{(i-1)}\}\)

- M-Step: Obtain \(\hat{\theta}^{(i)} = \max_{\theta} \{Q(\theta \mid \hat{\theta}^{(i-1)})\}\)

until convergence either in \(\hat{\theta}^{(i)}\) or in \(\log(L(\theta \mid W))\)

In Section 4.4, \(W_{\mathrm{obs}}\) corresponds to the data \(\mathbf{Z}\), while \(W_{\mathrm{mis}}\) corresponds to the coefficients \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}\).

4.4.2 Random Effects with Spatial Basis Functions

Consider the case where the of the spatio-temporal process are functions of space only and their random coefficients are indexed by time:

\[ Y(\mathbf{s};t_j) = \mathbf{x}(\mathbf{s};t_j)'\boldsymbol{\beta}+ \sum_{i=1}^{n_\alpha} \phi_i(\mathbf{s}) \alpha_{i}(t_j) + \nu(\mathbf{s};t_j),\quad j=1,\ldots,T, \tag{4.29}\]

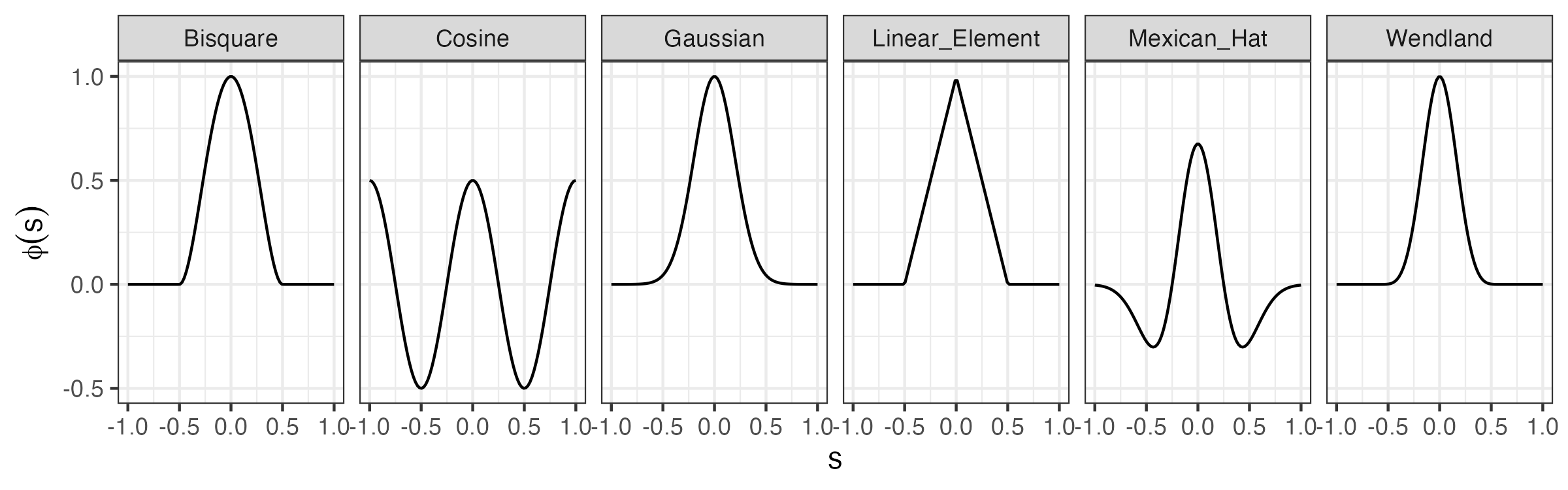

where \(\{\phi_i(\mathbf{s}): i=1,\ldots,n_\alpha;\ \mathbf{s}\in D_s\}\) are known spatial , \(\alpha_{i}(t_j)\) are temporal random processes, and the other model components are defined as above. We can consider a wide variety of spatial for this model, and again these might be of reduced rank, of full rank, or over-complete. For example, we might consider complete global (e.g., Fourier), or reduced-rank empirically defined (e.g., EOFs), or a variety of non-orthogonal bases (e.g., Gaussian functions, wavelets, bisquare functions, or Wendland functions). We illustrate a few of these in one dimension in Figure 4.7 (see also Section 3.2). It is often not important which basis function is used; still, one has to be careful to ensure that the type and number of are flexible and large enough to model the true dependence in \(Y\) (and the data \(\mathbf{Z}\)). This requires some experimentation and model diagnostics (see, for example, Chapter 6).

Assuming interest in the spatio-temporal dependence at \(n\) spatial locations \(\{\mathbf{s}_1,\ldots,\mathbf{s}_n\}\) and at times \(\{t_j: j=1,2,\ldots,T\}\), we can write model Equation 4.29 in vector form as

\[ \mathbf{Y}_{t_j} = \mathbf{X}_{t_j} \boldsymbol{\beta}+ \boldsymbol{\Phi}\boldsymbol{\alpha}_{t_j} + \boldsymbol{\nu}_{t_j}, \tag{4.30}\]

where \(\mathbf{Y}_{t_j}= (Y(\mathbf{s}_1;t_j),\ldots,Y(\mathbf{s}_n;t_j))'\) is the \(n\)-dimensional process vector, \(\boldsymbol{\nu}_{t_j} \; \sim \; Gau({\mathbf{0}},\mathbf{C}_\nu)\), \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}_{t_j} \equiv (\alpha_{1}(t_j),\ldots,\alpha_{n_\alpha}(t_j))'\), \(\boldsymbol{\Phi}\equiv (\boldsymbol{\phi}(\mathbf{s}_1),\ldots,\boldsymbol{\phi}(\mathbf{s}_n))'\), and \(\boldsymbol{\phi}(\mathbf{s}_i) \equiv (\phi_1(\mathbf{s}_i),\ldots,\phi_{n_\alpha}(\mathbf{s}_i))'\), \(i=1,\ldots,n\). An important question is then what the preferred distribution for \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}_{t_j}\) is.

It can be shown that if \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}_{t_1}, \boldsymbol{\alpha}_{t_2},\ldots\) are independent in time, where \(\boldsymbol{\alpha}_{t_j} \sim iid \; Gau({\mathbf{0}},\mathbf{C}_\alpha)\), then the marginal distribution of \(\mathbf{Y}_{t_j}\) is \(Gau(\mathbf{X}_{t_j} \boldsymbol{\beta}, \boldsymbol{\Phi}\mathbf{C}_\alpha \boldsymbol{\Phi}' + \mathbf{C}_\nu)\), and \(\mathbf{Y}_{t_1}, \mathbf{Y}_{t_2},\ldots\) are independent. Hence, the \(nT \times nT\) joint spatio-temporal covariance matrix is given by the , \(\mathbf{C}_Y = \mathbf{I}_T \otimes (\boldsymbol{\Phi}\mathbf{C}_\alpha \boldsymbol{\Phi}' + \mathbf{C}_\nu)\), where \(\mathbf{I}_T\) is the \(T\)-dimensional identity matrix (see Note 4.1). So the independence-in-time assumption implies a simple separable spatio-temporal dependence structure. To model a more complex spatio-temporal dependence structure using spatial-only , one must specify the model for the random coefficients such that \(\{\boldsymbol{\alpha}_{t_j}: j=1,\ldots,T\}\) are dependent in time. This is simplified by assuming conditional temporal dependence (dynamics) as discussed in Chapter 5.

4.4.3 Random Effects with Temporal Basis Functions

We can also express the spatio-temporal random process in terms of temporal and spatially indexed random effects:

\[ Y(\mathbf{s};t) = \mathbf{x}(\mathbf{s};t)' \boldsymbol{\beta}+ \sum_{i=1}^{n_\alpha} \phi_{i}(t) \alpha_i(\mathbf{s}) + \nu(\mathbf{s};t), \tag{4.31}\]

where \(\{\phi_{i}(t): i=1,\ldots,n_\alpha;\ t \in D_t\}\) are temporal and \(\{\alpha_i(\mathbf{s})\}\) are their spatially indexed random coefficients. In this case, one could model \(\{\alpha_i(\mathbf{s}): \mathbf{s}\in D_s;\ i=1,\ldots,n_\alpha\}\) using multivariate geostatistics. The temporal-basis-function representation given in Equation 4.31 is not as common in spatio-temporal statistics as the spatial-basis-function representation given in Equation 4.29. This is probably because most spatio-temporal processes have a scientific interpretation of spatial processes evolving in time. However, this need not be the case, and temporal are increasingly being used to model non-stationary-in-time processes (e.g., complex seasonal or high-frequency time behavior) that vary across space.

Example Using Temporal Basis Functions

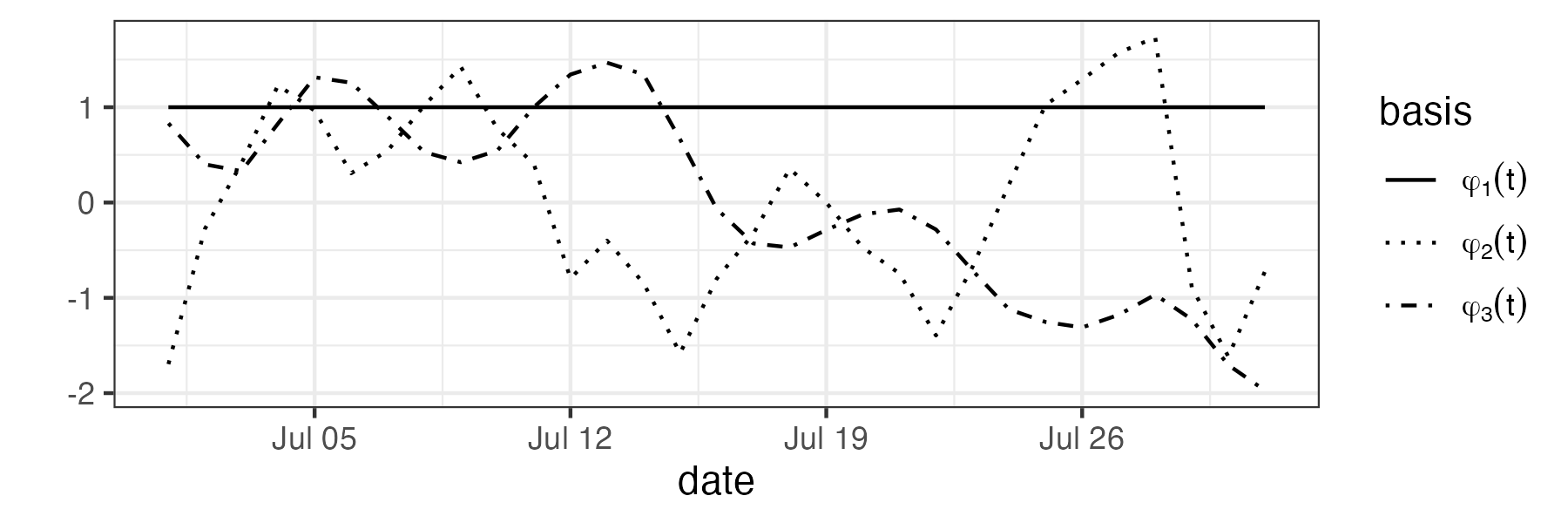

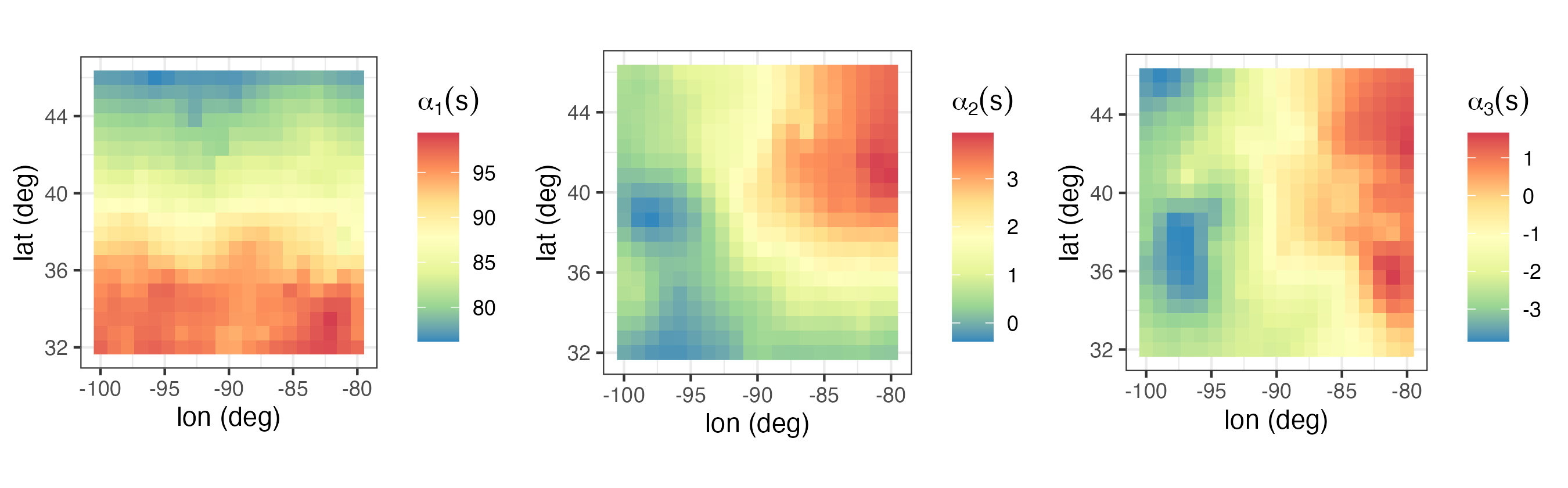

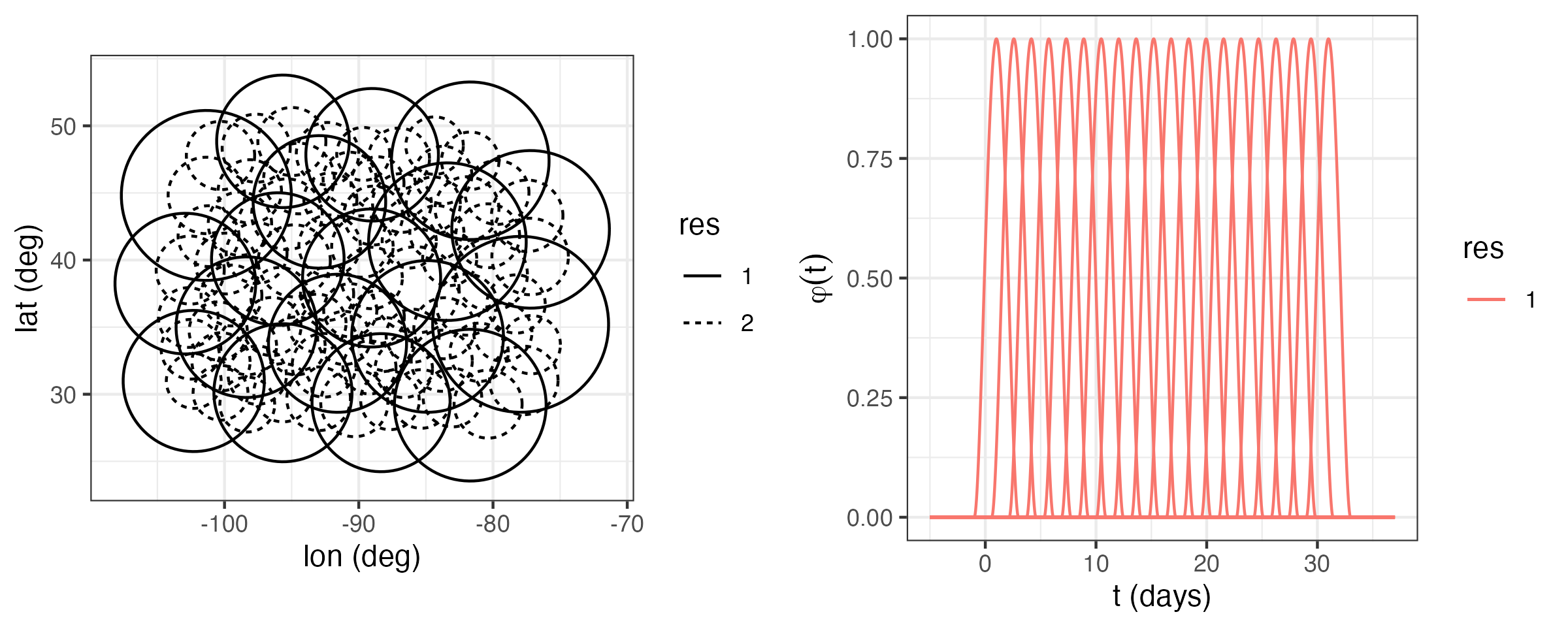

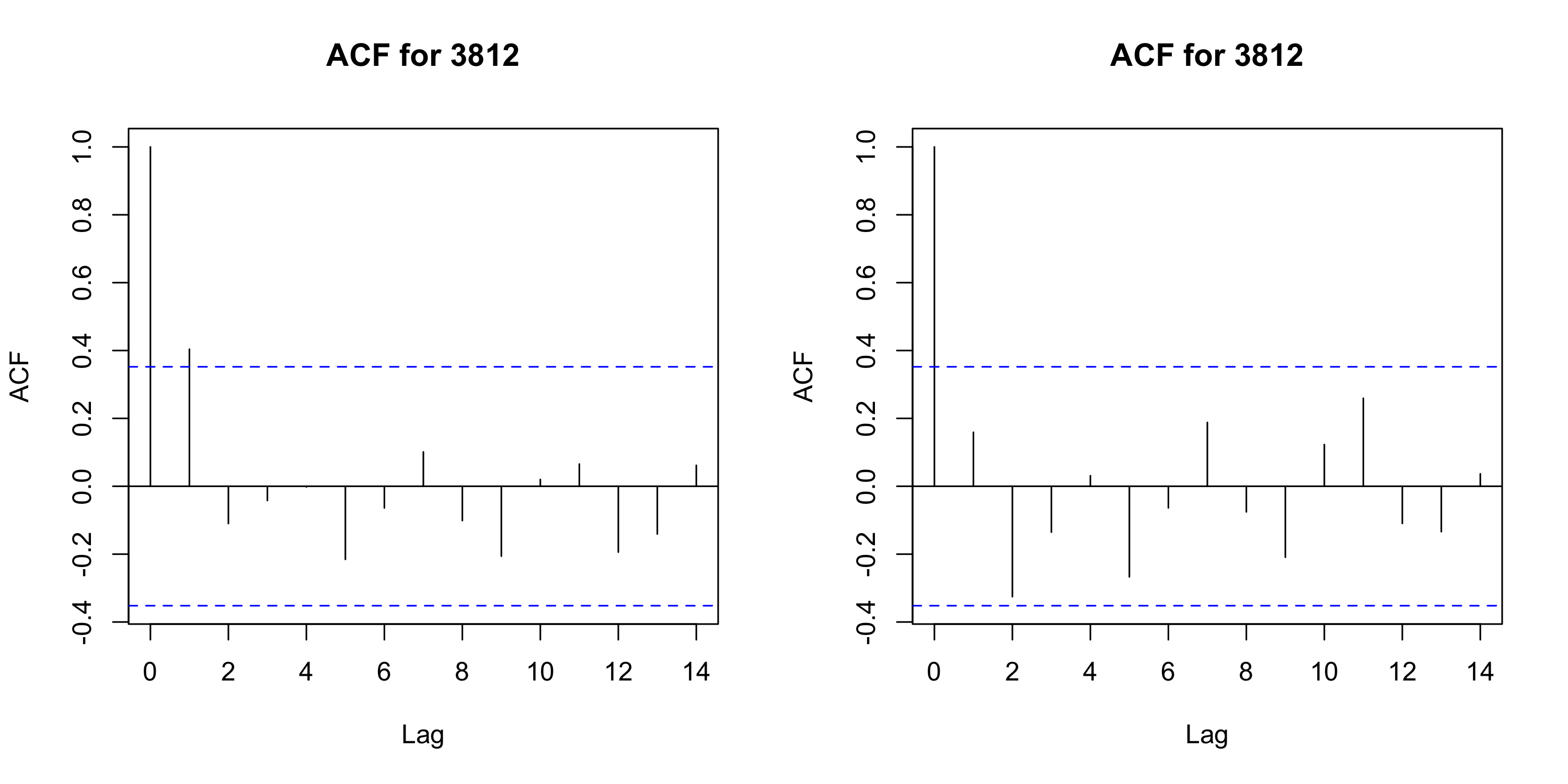

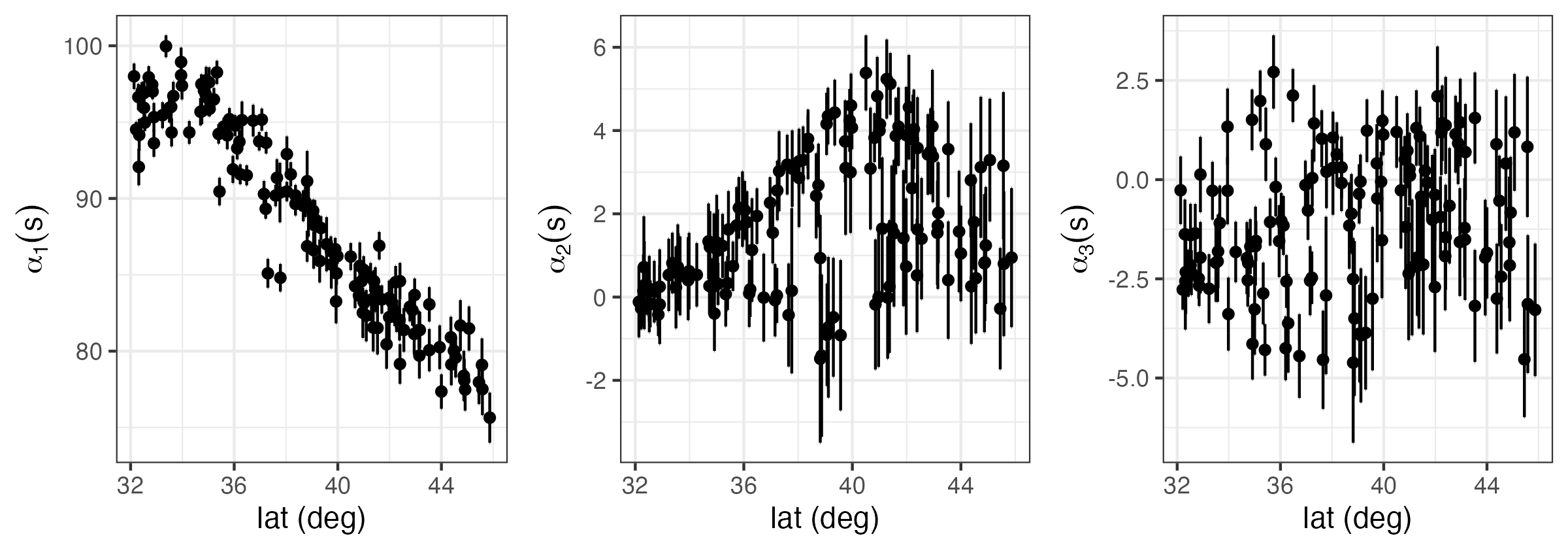

Spatio-temporal modeling and prediction using temporal can be carried out with the package SpatioTemporal (see Lab 4.3). In the top panel of Figure 4.8 we show the three temporal used to model maximum temperature in the NOAA data set. These were obtained following a procedure similar to EOF analysis, which is described in Note 2.2. Note that the basis function \(\phi_1(t) = 1\) is time-invariant.

Once \(\phi_1(t), \phi_2(t)\), and \(\phi_3(t)\) are selected, estimates (e.g., ordinary least squares) of \(\alpha_1(\mathbf{s}), \alpha_2(\mathbf{s})\), and \(\alpha_3(\mathbf{s})\) can be found and used to indicate how they might be modeled. For example, in Lab 4.3 we see that while both \(\alpha_1(\mathbf{s})\) and \(\alpha_2(\mathbf{s})\) have a latitudinal trend, \(\alpha_3(\mathbf{s})\) does not. Assigning these fields exponential covariance functions, we obtain the models:

\[ E(\alpha_1(\mathbf{s})) = \alpha_{11} + \alpha_{12}s_2, \quad \textrm{cov}(\alpha_1(\mathbf{s}), \alpha_1(\mathbf{s}+ \mathbf{h})) = \sigma^2_1 \exp(-\|\mathbf{h}\|/r_1), \tag{4.32}\]

\[ E(\alpha_2(\mathbf{s})) = \alpha_{21} + \alpha_{22}s_2, \quad \textrm{cov}(\alpha_2(\mathbf{s}), \alpha_2(\mathbf{s}+ \mathbf{h})) = \sigma^2_2 \exp(-\|\mathbf{h}\|/r_2), \tag{4.33}\]

\[ E(\alpha_3(\mathbf{s})) = \alpha_{31}, \quad\qquad~~~~~~~ \textrm{cov}(\alpha_3(\mathbf{s}), \alpha_3(\mathbf{s}+ \mathbf{h})) = \sigma^2_3 \exp(-\|\mathbf{h}\|/r_3), \tag{4.34}\]

where \(s_2\) denotes the latitude coordinate at \(\mathbf{s}= (s_1, s_2)'\), \(r_1, r_2\), and \(r_3\) are scale parameters, and \(\sigma^2_1, \sigma^2_2\), and \(\sigma^2_3\) are stationary variances. We further assume that \(\textrm{cov}(\alpha_k(\mathbf{s}),\alpha_{\ell}(\mathbf{s}')) = 0\) for \(k \neq \ell\), which is a strong assumption.